2024 has been an incredibly successful year for far-right populists in Western countries. They have achieved shockingly high results in elections across Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Belgium, and even in the United States, where Donald Trump’s Republican Party has mobilized its supporters around ultra-conservative, anti-immigration rhetoric. Unlike in 2015, when the surge in right-wing populism was tied to a migration crisis, there appears to be no immediate political cause for the current wave. A number of experts have suggested that economies in the West actually lack sufficient migrant labor, and that excessive restrictions are now hindering growth. Research by The Insider indicates that economic factors — particularly inflation — are the primary drivers behind the rise of far-right and far-left sentiments. Those grappling with inflation often seek scapegoats and, influenced by far-right populists, frequently direct their blame toward immigrants. Regions with larger migrant populations notably tend to show lower levels of xenophobia.

Content

The rise of radicalism and populism

The real culprit — inflation, not migration

Historical parallels

Migration as an antidote to xenophobia

High unemployment keeps the left busy

Growing political polarization is a threat to democracy

The rise of radicalism and populism

The resurgence of radical parties in Europe began a few years ago, but 2024 represents a breakthrough for extremes on both ends of the political spectrum. Major victories were scored by Italy's Brothers of Italy (“Fratelli d'Italia”), France's National Rally (“Rassemblement national” or RN), Germany's Alternative for Germany (“Alternative für Deutschland” or AfD), and multiple others. The peak of the far-right success came on Sept. 29, when Austria's Freedom Party (“Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs” or FPÖ) secured the most votes in national elections. The party's leader, Herbert Kickl, has been called a Nazi and is known for advocating the “remigration” of non-native Austrians in order to create a more “homogeneous” society.

There are both political and economic reasons behind the far-right’s success. The ideology of modern far-right movements combines radical social policies with populist economic rhetoric. Generally, they are known to oppose immigration — especially from Islamic countries — and stand against a unified Europe while supporting protectionism within national borders. Far-right parties present themselves as the defenders of “native” citizens, who are said to have suffered from crises and are disillusioned with current leadership.

“Indigenous [Dutch] people are being ignored because of the mass immigration,” Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch right-wing “Party for Freedom,” told the BBC last year. “We have to think about our own people first now. Borders closed. Zero asylum-seekers.”

In Portugal, a recent bid to simplify the process for obtaining humanitarian visas was thwarted in October 2024 after fierce resistance from the anti-immigration party Chega. Members of the movement branded the proposal as being championed by “traitors,” leading to the humanitarian visa initiative’s defeat in parliament.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

“Our own people first” and “closed borders” are a typical far-right rallying cry.

It is not only immigration issues that drive support for populists. Almost all far-right radicals are skeptical of spending public money on programs aimed at fighting climate change, with some entirely rejecting regulations aimed at environmental protections.

Dating back to the financial crisis of 2008, the resurgence of far-right populism in Europe has often been attributed to economic concerns, which only deepened during the coronavirus pandemic. Others blame the rise on migration surges triggered by conflicts in the Middle East, North Africa, and, in 2022, Ukraine. However, while far-right parties occasionally engage in anti-Ukrainian rhetoric, it is not their main political focus, as public opinion in Europe and the U.S. tends to support Ukraine. General xenophobic sentiments sometimes target Arab Muslim migrants, exhibit antisemitism, or, as in the U.S., focus on exaggerated images — as when candidate Trump infamously claimed that migrants were eating regular Americans’ household dogs and cats. But such sentiments appear to be expressions of accumulated dissatisfaction rooted in a range of different issues. Examining the timing and locations of spikes in radicalism and populism reveals that these surges often follow shifts in socio-economic indicators — and inflation remains the strongest predictor of rising far-right popularity.

The real culprit — inflation, not migration

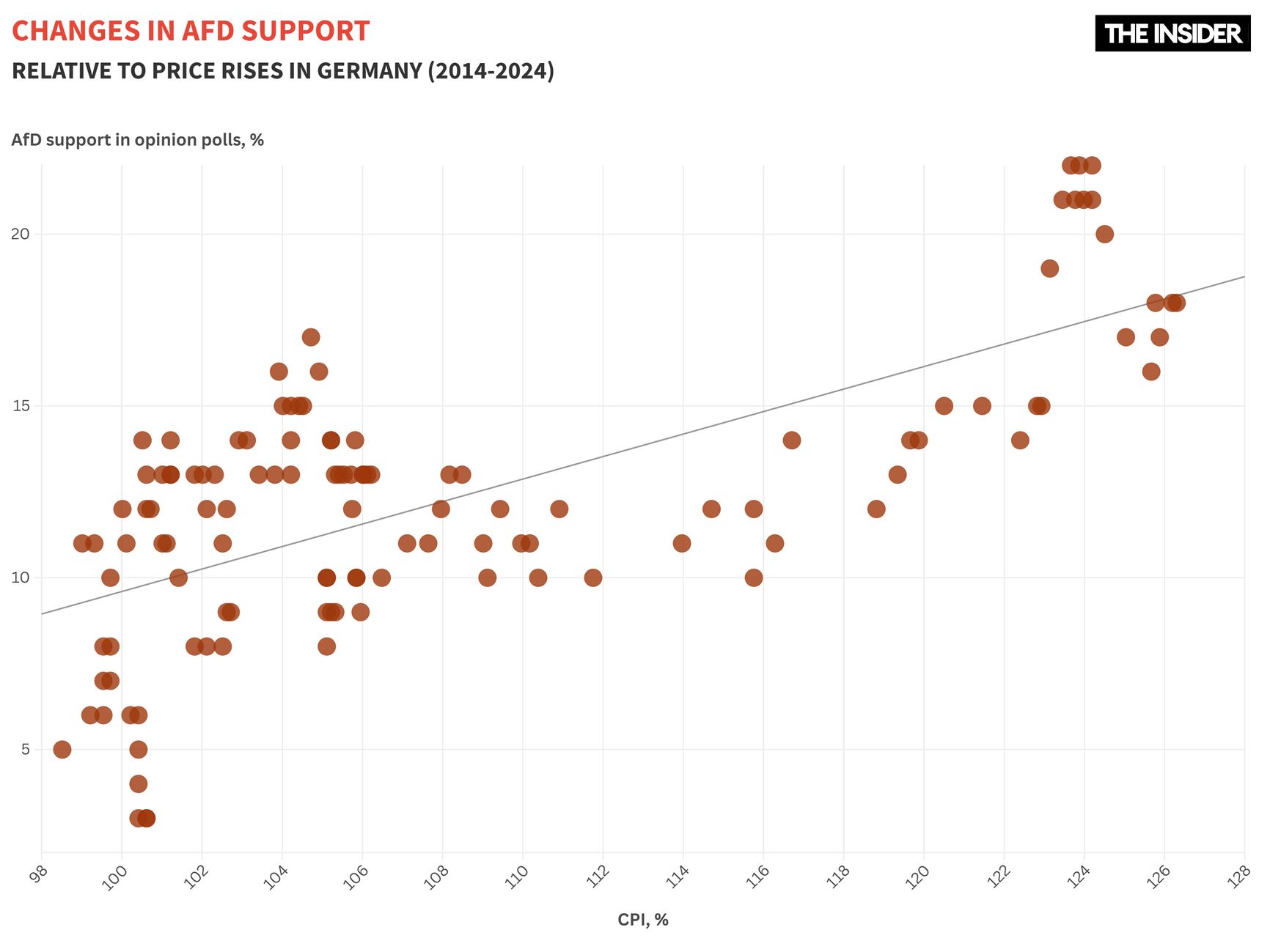

The Insider’s analysis of monthly changes in Germany's consumer price index and support for the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) over a ten-year period reveals that a 1% rise in prices coincides with a 0.32% increase in AfD’s support. There is also a noticeable regional correlation between levels of poverty and support for the far right — support for the right is increasing in areas with the highest numbers of people living below the poverty line. When poverty risk increases by 1%, AfD support grows by an average of 0.6%.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

A similar trend is observed in neighboring France: the far-right National Rally party, which secured the majority of votes in local elections for the European Parliament, is also gaining traction amid rising inflation. Data analyzed by The Insider shows that over the past six years, a 1 percentage point increase in prices leads to a 0.58% rise in support for the party, with a strong correlation between the two.

Similarly, support for the Giorgia Meloni-led Brothers of Italy, which won a majority in elections to the European Parliament, is highly correlated with inflation. A ten-year analysis shows that a 1% rise in prices aligns with a 1.24% increase in support for the party.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

Calculations by The Insider confirm a link between inflation and the rising popularity of far-right movements in Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

This pattern repeats across Hungary, Austria, and the Czech Republic, where rising inflation boosts the popularity of far-right parties.

Does this correlation indicate causation? The inverse hypothesis — that far-right popularity causes inflation — can be dismissed, as these parties have rarely been in power during the periods examined, limiting their impact on policy. While a third factor might theoretically link inflation to support for far-right parties, the simplest explanation for the broad correlation is that inflation-related declines in living standards generate dissatisfaction, a sense of uncertainty about the future, and a heightened openness to rhetoric that appeals to fears and threats — and targets scapegoats. Migrant groups provide a convenient image of an “enemy” to be blamed for economic troubles (in the past, these “enemies” were often Jewish bankers; now, they are Arab immigrants).

Historical parallels

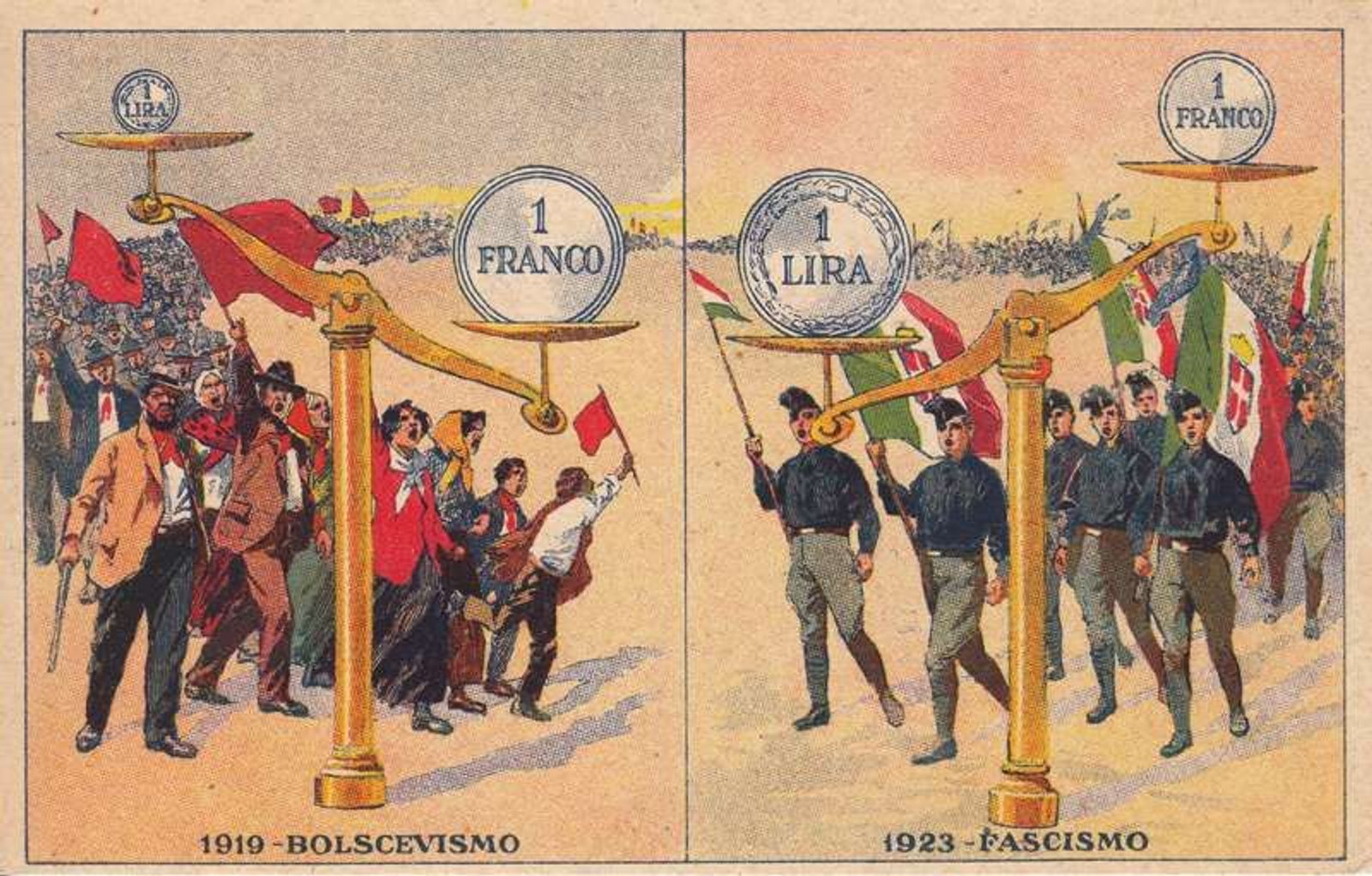

The link between far-right popularity and inflation-induced economic decline has historical precedents, most notably in interwar Europe.

Italy’s “National Fascist Party,” led by Benito Mussolini, benefited from the crisis that engulfed the country following World War I. Italy's wartime governments had printed money to finance military expenses, leading to rampant inflation, and by the end of 1920, the lira was worth only one-sixth of its 1913 value, leaving thousands of people — particularly those with fixed incomes — on the brink of survival. The post-war coalition governments were weak and could do little other than suppress strike movements by force.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

Benito Mussolini (center) during the March on Rome in October 1922, which marked the beginning of his rule.

Getty Images

Economic turmoil facilitated the rise of radical nationalist movements — including the one represented by Mussolini’s party, which garnered 19.1% of votes in 1921 and 65% by 1924, following their seizure of power. Combating inflation and stopping the devaluation of the lira were among the fascists' main campaign promises. Disillusioned by socialist and communist failures, many Italians were willing to support any force capable of imposing order — even when it meant blackshirts violently attacking newspapers and trade unions.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

Fascist election campaign leaflet from 1924.

Germany faced a similar, albeit harsher, situation. A decade before Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, Germany experienced one of history’s worst bouts of hyperinflation, accompanied by a banking collapse, economic deflation, mass unemployment, debt moratoriums, currency controls, social unrest, and extreme political tension. While various factors contributed to the Nazis’ ascent, most historians agree that hyperinflation and its impact on living standards were critical conditions behind their popularity (1, 2).

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

In 1923, a banknote worth 100 billion German marks could buy about 1 kilogram (2.2 lbs) of meat.

Fighting inflation was one of Hitler's key campaign promises, but equally important to his rise was the creation of an enemy — Jews were accused of “corrupting German blood” and of being “parasites” that threatened the overall health of the so-called “national community” (Volksgemeinschaft). And the tradition continued into the next century. In 2023, with inflation reaching a 40-year high, Donald Trump repeatedly accused immigrants of “poisoning the blood of our country” — and one year later won the U.S. presidency for the second time.

Historical examples extend beyond Nazi Germany and Italian fascism. During the Great Depression, support for the far right surged in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Spain, Switzerland, and even the UK, where Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, promised isolationist economic policies to alleviate the crisis. The movement had attracted approximately 50,000 members by 1934. In the United States, local Nazis held massive rallies at Madison Square Garden up until the outbreak of World War II.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

A mass gathering of 20,000 members of the pro-Nazi League of the Friends of the New Germany took place at New York's Madison Square Garden on May 17, 1934.

The link between financial crises and far-right radicalism is not limited to Western nations. In Japan, a financial crisis triggered by a 1923 earthquake led to a surge in militarism and a unique brand of Japanese fascism. In 1973, Chile faced hyperinflation, setting the stage for dictator Augusto Pinochet’s rise to power (though he failed to curb inflation). And here, Argentina offers a fresh example: right-wing populist Javier Milei, a self-proclaimed “minarchist” who opposes migration and abortion, took office with a radical economic program amid annual inflation exceeding 200%. Unlike Pinochet, Milei has had some success in slowing inflation, with price growth dropping from a monthly rate of 25% in December 2023 to 3% this past September (though it remains too early to gauge the long-term impact of his harsh measures).

Migration as an antidote to xenophobia

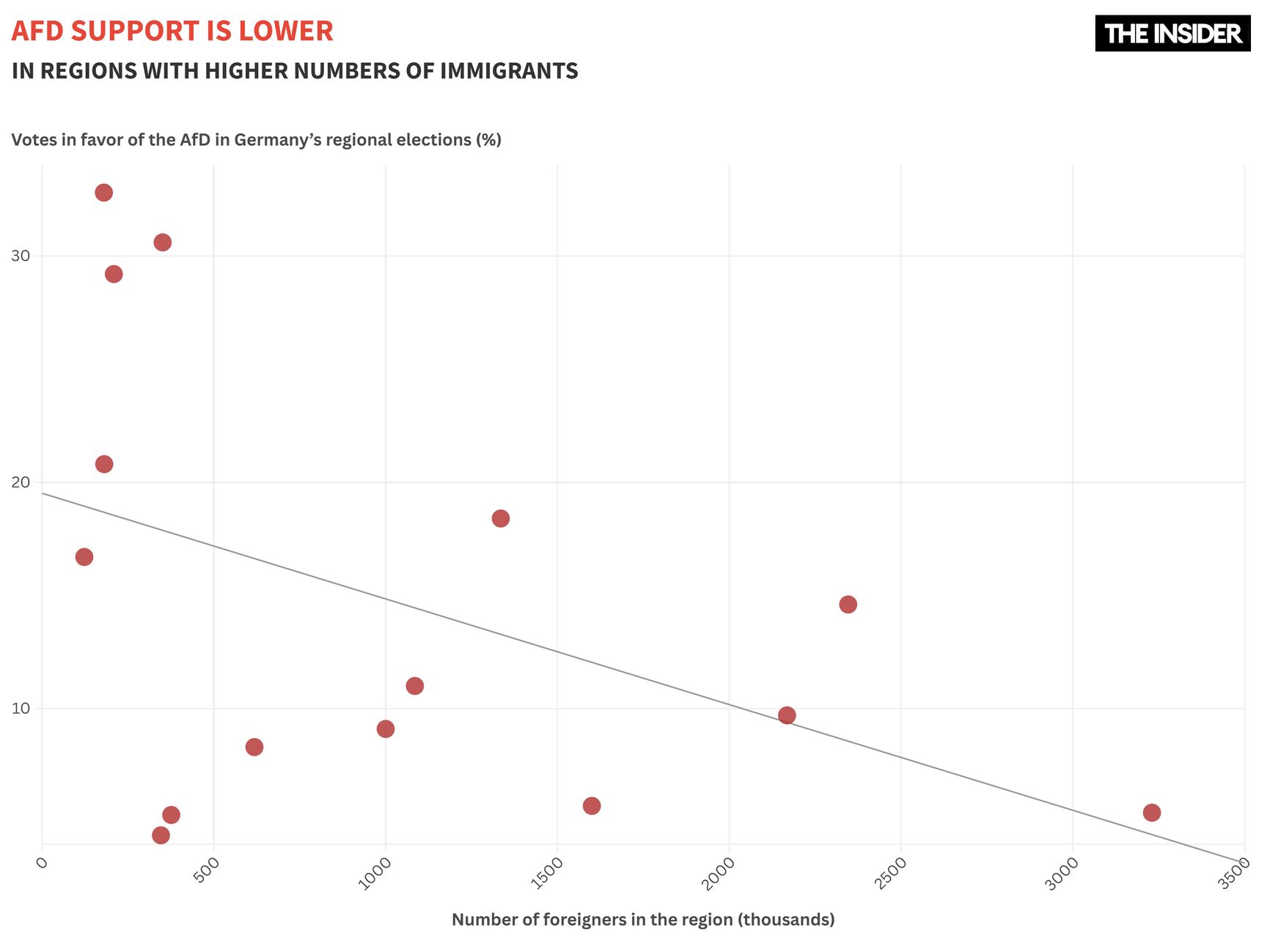

The rise of far-right populism is often linked to migration issues, but the reality is more complex. In Italy, there is a slight positive correlation, whereas in Germany, an inverse relationship exists: regions with higher numbers of foreigners show greater skepticism towards the far-right.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

A similar trend appears in Finland, where every 1,000-person increase in foreign residents results in a 0.22% decrease in support for the far-right “Finns” party (formerly known as the “True Finns”). Even in the U.S., every 100,000-person increase in a state’s foreign population leads to an average 0.17% reduction in Republican support.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.

In areas with a significant migrant population, support for far-right parties tends to be lower, as personal interactions help diminish biases.

This “anomaly” can be explained by the intergroup “contact hypothesis” formulated by American psychologist Gordon Allport in 1954. According to Allport, interpersonal contact can be one of the most effective ways to reduce prejudice between members of majority and minority groups. Properly structured interaction helps break down stereotypes, biases, and discrimination, promoting healthier intergroup relations. As a result, far-right xenophobic rhetoric may fail to resonate in areas that are home to large numbers of immigrants.

High unemployment keeps the left busy

The methods of left-wing populists often resemble those of their counterparts on the right — they position themselves against elites and current governments, frequently appealing to the “common people.” However, while doing so, they advocate for anti-capitalism, anti-corporatism, democracy, and social justice, often without considering the potential impact on economic growth.

Numerous studies (1, 2, 3) demonstrate a correlation between unemployment and the popularity of far-left and left-wing populists. Calculations by The Insider clearly illustrate this connection. For instance, in the United States, a 1% increase in a state's unemployment rate corresponds to a 2.9% rise in support for Democrats in that state. Similarly, in Germany, a 1% rise in regional unemployment results in a 1.57% increase in support for the left-wing party.

Argentina provides a telling example of how right-wing policies can affect unemployment rates. Javier Milei has managed to tame inflation, but at the cost of a 2% increase in unemployment during the first quarter of his presidency. In the U.S., unemployment also tends to rise under Republican presidents — by an average of 1.1% during their terms — while it decreases by an average of 0.8% when a Democrat is in the White House.

Growing political polarization is a threat to democracy

During periods of economic and political crises, voters often shift from choosing between more traditional parties of the center-right and center-left and opt for more extreme options on the political spectrum. Both far-left and far-right movements offer alternatives to traditional politics, and when problems arise, many people blame those in power no matter what the underlying cause of the hardships might be.

As a result, the extremes often start to resemble one another. For example, many modern far-right groups — from France's National Rally to Germany's AfD — advocate for higher government intervention in the economy (which is fairly unusual for the right) and even for large-scale social benefits. However, these hand-outs are often reserved for “their own,” sometimes defined by blood, promoting what can be described as “social chauvinism.”

Far-right populists frequently incorporate elements of left-wing rhetoric (and vice versa) into their agendas, attempting to cater to a broader electorate. The success of far-right populist parties in recent decades stems from their blend of economically left-leaning policies with culturally right-wing positions.

The central dividing question between these political extremes is often not about economics, but about whether nationalism represents a solution to the upheavals of globalization — such as mass migration and economic instability — or whether it poses a threat to freedom and democracy.

The 2008 global financial crisis played a significant role in these developments. According to data from the V-Dem Institute, political polarization in Europe had been steadily declining since the end of World War II, but it began rising again after 2008, reaching levels last year that were comparable to those seen in the mid-20th century. A similar trend has been observed in the U.S., where polarization also accelerated significantly after 2008.

While neither the impatient far-right nor the anti-establishment far-left currently enjoys enough support to become a truly destructive force in countries that enjoy strong institutional foundations, ignoring their growing influence could lead to the erosion of established norms and place democracy itself at risk.

A minarchist supports limiting the role of the state to its essential functions, focusing solely on protecting individual freedoms and private property rights.