In April, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party surged to the top of German opinion polls for the first time in the country’s postwar history. According to an INSA survey, the AfD tied for first place with the Christian Democrats at 25% support. Meanwhile, Forsa placed the AfD alone at the top with 26%. Notably, this development has less to do with AfD’s popularity, which has grown by just 2–3% over the past year. Instead, it is largely the result of a marked decline in support for AfD’s mainstream rivals. A mere two months after federal elections, the emerging governing coalition — a combination of the conservatives and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) — is backed by only 40% of respondents. The reasons behind the AfD’s relative rise are many: a long-repressed demand for radicalism, the mainstream parties’ failure to compete on social media, and growing disillusionment with establishment politics. Experts warn that if the new coalition fails to meet current challenges, the AfD’s popularity will only continue to grow.

Content

What German voters see in the AfD — and why

The eastern factor

Fault lines

The AfD in power?

This article was originally published in Russian on April 30, 2025.

What German voters see in the AfD — and why

The AfD’s current standing in the polls is not the party’s only “first.” Founded 12 years ago, the party has become the first truly significant far-right force in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany and the first to achieve consistent success across all levels of elections — municipal, regional, federal, and European.

So how did a modest initiative by little-known ultraconservatives and Euroskeptic academics evolve into a major national political force, with every fourth seat in the Bundestag now held by one of its members?

Understanding the AfD’s success requires an exploration of the specifics underlying the German political system — more precisely, that of West Germany. The Federal Republic was built on the repudiation of Nazism and a firm rejection of authoritarianism, militarism, and xenophobia. Parliamentary democracy was seen as the only viable model for the new state, andthe government and civil society reacted harshly to any attempt to promote far-right ideology. While other Western European countries already had notable far-right parties with parliamentary representation, Germany cultivated conditions that made it virtually impossible for such movements to compete and successfully. For decades after the end of WWII, extremist rhetoric in Germany was deeply marginalized.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

Both the German government and civil society had long reacted harshly to any attempt to promote far-right ideology.

Reunification did not substantially change this dynamic. While small far-right parties gained limited representation in some regions, they remained politically insignificant.

The CDU/CSU bloc encompassed both moderate conservatives and more right-leaning citizens. Far-right ideas were often channeled through internal party factions. For example, Alexander Gauland, a far-right figure who once held high office in Hesse, was a member of the Christian Democrats. The Bundestag conservative caucus included Martin Hohmann, known for antisemitic remarks that led to his expulsion, and Erika Steinbach, a prominent critic of Germany’s migration policy. All three are now with the AfD — Gauland is honorary party chairman, and Hohmann was an MP for the AfD until recently.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

Honorary Chairman of the AfD, Alexander Gauland.

The AfD’s rise to its current popularity was made possible by four key factors.

First, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) underwent significant transformation during the tenure of Chancellor Angela Merkel. The party shifted away from its traditional conservative stance, adopting centrist and, in some respect, even center-left positions. Voters to the right of the CDU found it increasingly difficult to accept Merkel’s decisions — most notably her acceptance of Syrian refugees during the migration crisis and her approval of multibillion-euro aid packages to countries like Greece during the financial crisis. For these voters, the CDU ceased to be a political home, and resulting turbulence and uncertainty in the government’s direction became fertile ground for the AfD to take root.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

Under Merkel, the CDU shifted away from its traditional conservative stance, adopting centrist and, in some respect, even center-left positions.

Second, other German political parties in the 2010s failed to mount strong opposition to Merkel on key domestic and foreign policy issues. Three of Merkel’s four administrations were grand coalitions with the Social Democrats (SPD), making them a dominant force on the political stage. But rather than seeking to increase their political capital by opposing the coalition, other mainstream parties generally aligned with government decisions. This led some Germans to feel entirely unrepresented in the political system.

Third, amid a rapidly evolving global landscape, there has been a rising appetite for radicalism. The anti-fascist “vaccine” of the 20th century began to lose its potency, and increasing numbers of Germans were willing to broach subjects previously deemed off-limits. Against the backdrop of a global pandemic — and, later, a major war in Europe — the public’s desire for clear-cut answers and identifiable culprits intensified.

Finally, social media began playing a decisive role in shaping public opinion. While mainstream democratic parties were slow to adapt to the digital landscape — during a 2013 joint press conference with Barack Obama, Merkel even described the internet as “uncharted territory for us” — the AfD quickly immersed itself in this space. It aggressively promoted its narratives both through official channels and via its networks of supporters online.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

The AfD quickly insinuated itself in the digital landscape, promoting its narratives both through official channels and via its networks of supporters online.

The AfD also benefited from Germany’s domestic political crisis. By the end of its term, the “traffic light coalition” of the SPD, Greens, and Free Democrats was deeply unpopular. Public disputes among coalition members only reinforced voters’ perception that something was fundamentally wrong. By mid-2024, a majority of Germans were calling for new elections, which were ultimately held in February 2025.

Such snap elections are rare in Germany — this was only the fourth instance since 1949 — and they typically put stress on the political system. Though the process, from the dismissal of Finance Minister Christian Lindner to the election itself, unfolded entirely within the bounds of German law, it sent a troubling signal to the public.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

Despite winning the election, Friedrich Merz lost 9 percentage points in his personal approval rating compared to the previous year.

Adding to the AfD’s momentum was the decline in popularity of conservative leader Friedrich Merz. Many right-leaning voters who were reluctant to support the AfD due to its perceived anti-democratic tendencies had viewed Merz as a right-conservative alternative to Olaf Scholz’s government. But a series of decisions — supporting the softening of Germany’s constitutional “debt brake” despite campaign promises, forming a coalition with the SPD, and compromising on migration, labor market, and taxation issues — damaged his credibility. Though Merz has just been approved chancellor — in an unprecedented second round of voting — he has seen his year-on-year trust rating fall by nine percentage points. Today, only 21% of Germans express confidence in Merz, and many among the disillusioned right-wing electorate have shifted their support to the AfD.

The eastern factor

Contrary to popular belief, the Alternative for Germany is not solely an East German party. Founded by West Germans, the AfD now performs strongly across all regions of the country. In the 2025 elections, it nearly doubled its vote share in major western states compared to 2021 — scoring 19% in Bavaria, 19.8% in Baden-Württemberg, and 16.8% in North Rhine–Westphalia. At the same time, it achieved clear first-place finishes in all five eastern regions, with results ranging from 32.5% to 38.6% — comparable to the CDU’s and SPD’s best historical performances.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

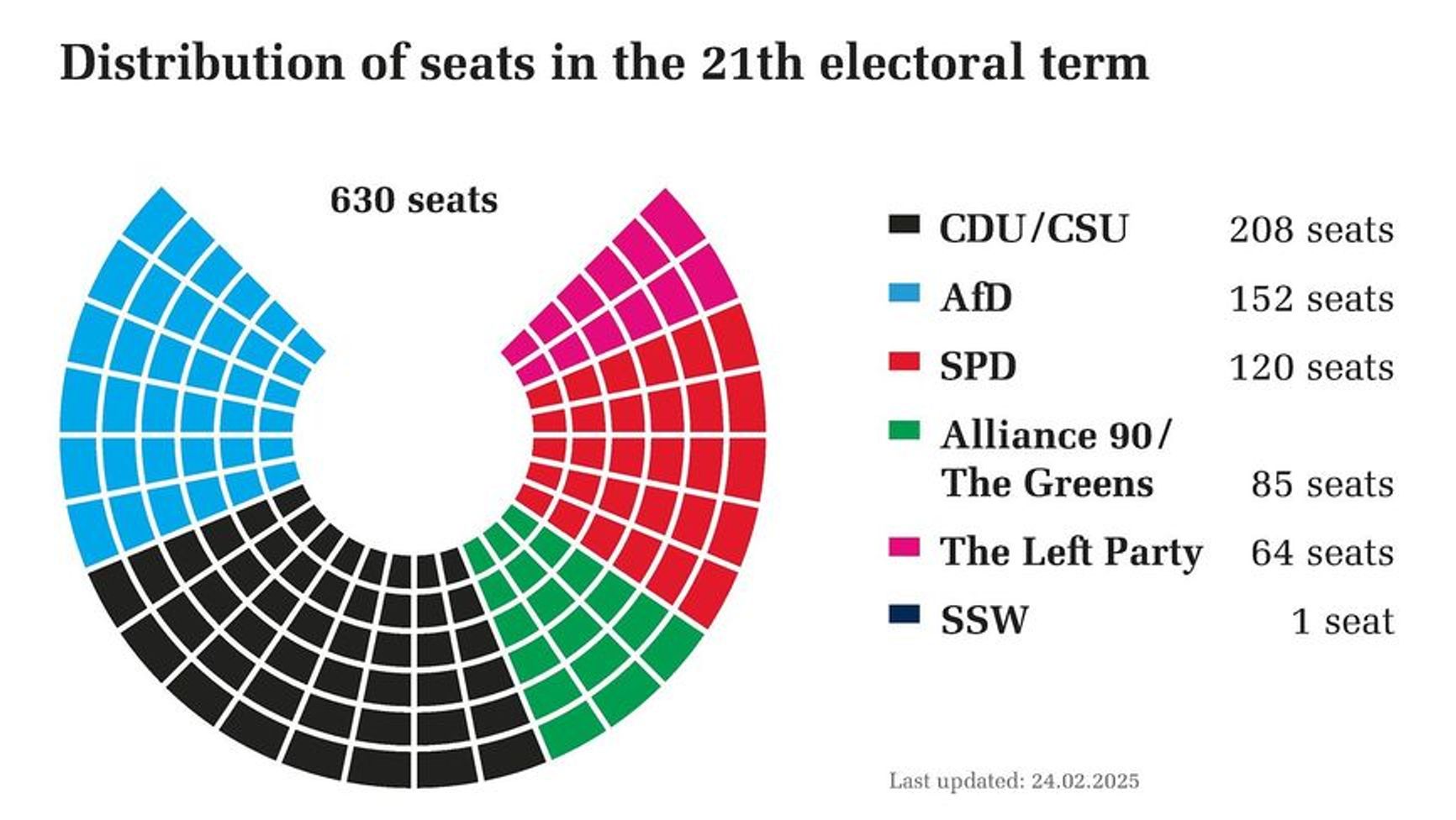

Seat distribution in the Bundestag following the 2025 snap elections in Germany.

The data from specific districts in the east is even more extraordinary: the AfD won 47 out of 50 constituencies, an unprecedented feat in German political history. Many experts now consider the AfD to be a “people’s party” in eastern Germany — a status previously reserved only for the Conservatives and Social Democrats. In states such as Thuringia, Saxony, Brandenburg, and Saxony-Anhalt, the AfD has significantly strengthened its local branches, creating effective, grassroots networks closely connected to local communities and civic initiatives. In these regions, the AfD has not only achieved high parliamentary election results but also secured mayoral positions — such as in the historically significant tourist town of Jüterbog near Berlin.

The roots of AfD’s popularity in eastern Germany can be traced back to the recent past. In the German Democratic Republic (GDR) — the “first socialist state on German soil” — antifascism was a state doctrine. The existence of far-right ideology was officially denied and actively silenced, while civil society was heavily suppressed by the government.

Unlike West Germany, the GDR had no counterpart to the Federal Agency for Civic Education, a state institution that promoted democratic awareness and the ideals of tolerance. As a result, after reunification, residents of the eastern federal states proved especially susceptible to the “forbidden fruit” of far-right ideology.

Secondly, prior to 1990 the average East German had virtually no experience interacting with people of foreign origin. The GDR was ethnically homogenous; Soviet soldiers and Vietnamese workers lived in isolated communities, apart from the general population. In the multicultural reality of the newly reunified Germany, this lack of exposure among the population contributed to reactions that bordered on xenophobia and chauvinism.

Thirdly, despite the euphoria of the 1990s, which was followed by the stabilization and economic growth seen in the 2000s ever since, many East Germans still feel deeply dissatisfied and believe they are underrepresented in the country’s decision-making circles — be it in politics, finance, big business, science, culture, or education.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

Many East Germans still feel deeply dissatisfied and believe they are underrepresented in the country’s decision-making circles.

Sociological studies show that while a majority of eastern Germans are satisfied with their material well-being and generally view German reunification as a positive historical milestone, many still express resentment over what they perceive as unjustly low status in the federal hierarchy — which fuels a narrative of an “unfinished reunification.”

These sentiments often evolve into moral disengagement and a growing rejection of democracy as a viable system of governance. For example, a 2020 survey found that only 47% of Germans believed that East and West had become truly united, while 53% said that “the wall still exists in people’s minds.” In western Germany, 86% of respondents were satisfied with democratic institutions, compared to just 35.6% in the East — and only 7.2% among AfD supporters.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

A 2020 survey found that 53% of Germans believed that the country was still divided and that “the wall still exists in people’s minds.”

A lingering feeling of exclusion from political power, frayed connections with local politicians — especially in rural eastern areas — and rejection of the political agenda that AfD supporters believe is being forced upon them by mainstream parties, all contribute to the the far-right party’s rise. The party has cast itself as the “advocate of the East.”

Changing attitudes among key electoral blocs are also evident in district-level election results. In Cottbus–Spree-Neiße, located on the Polish border in Brandenburg and home to the second-largest city in the state, the SPD had long been dominant, with the Left Party as its primary competitor. In the 2021 elections, the SPD won the district handily, securing its seat in the Bundestag. But just three and a half years later, the landscape had changed dramatically. The AfD nearly doubled its share of the vote, reaching 39% and winning by a wide margin. The district’s new Bundestag representative is a far-right politician who received 42% of the vote.

Fault lines

Not long ago, Germany was seen as a model of parliamentary democracy. Today, however, one of the main dividing lines in German society is the public’s attitude toward democratic governance and authoritarian alternatives.

A comprehensive study presented in Leipzig in 2024 revealed a stark erosion of trust: only 42.3% of Germans said they were satisfied with the functioning of grassroots democratic institutions — the lowest reading ever recorded. In eastern Germany, that figure dropped to just 29.7% . The research also showed a notable rise in the number of respondents willing to accept authoritarian rule “in the name of national interests”: 15.2% would welcome a strongman leader, while 21.4% would support a one-party system claiming to “represent the interests of the people.”

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

Although the Alternative for Germany (AfD) operates within the boundaries of Germany’s legal framework and refrains from openly calling for regime change, its rhetoric and the behavior of its leaders clearly signal that they see themselves as the sole embodiment of the “national interest” — a message that resonates with nationalist-leaning voters.

Another axis of division lies in attitudes toward right-wing extremism and respect for the rule of law. The AfD has introduced the controversial concept of “remigration” into the public discourse — referring to the potential deportation of certain foreign-born residents, including those with legal status or even German citizenship. This reflects a readiness to disregard both national and international law in pursuit of the party’s goals — a stance that resonates with its core supporters.

Most experts now argue that it is no longer accurate to characterize the AfD simply as a protest party channeling the frustrations of the discontented. As Wolfgang Schroeder, a political scientist at the University of Kassel, observes: “People are no longer voting for the AfD just because they’re unhappy with the government. They’re doing it because they identify with the party as part of their social environment.” His colleague Wilhelm Heitmeyer is even more blunt, calling the notion of “protest voters” a form of self-deception on the part of the political establishment.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

“People are no longer voting for the AfD just because they’re unhappy with the government. They’re doing it because they identify with the party,” says political scientist Wolfgang Schroeder.

A further divide concerns political literacy. German political culture has long been marked by high voter turnout and thoughtful engagement with policy platforms. Traditionally, voters would read and compare party programs, assess the feasibility of proposals, and largely avoid populist appeals. But a January 2025 survey showed this tradition is weakening.

Only 19% of respondents had read party platforms in full, 60% read only summaries, and 21% didn’t read them at all. This indicates that sizable voting blocs are now making decisions based on emotions and personal impressions — precisely the demographic the AfD targets with its appeals to instinct and reaction.

Germany is also deeply divided over the issue of migration. According to a recent survey, more than a quarter of Germans consider migration and the integration of foreign nationals the country’s most important issue — second only to the state of the economy. Broadly speaking, the public splits into three camps: those who support the current, relatively welcoming approach toward migrants and asylum seekers; those who favor stricter entry and residency rules, as proposed by Friedrich Merz or in the softer version outlined in the CDU-SPD coalition agreement; and those who advocate for closing the borders entirely.

For the AfD, anti-migration rhetoric remains a central pillar of its political identity and a key driver of its electoral success. The party advocates for the mass deportation of undocumented migrants and a ban on asylum seekers arriving via so-called “safe countries.” While the AfD acknowledges Germany’s need for highly skilled foreign workers, it argues the country should explore ways to meet labor demands with its own citizens and reduce even these types of migration. In doing so, the far-right party has shown its clear willingness to violate both national and international law — demonstrating the kind of radicalism and uncompromising stance that appeals to its voter base.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”

The AfD’s most successful campaign theme is its stance against migration.

Foreign policy has also become a point of division, especially when it comes to Germany’s continued support for Ukraine. Public opinion splits into three camps: those who favor maintaining or increasing aid, those who want to end military support while continuing humanitarian assistance, and those who advocate ending all aid entirely. Some support military assistance but oppose the provision of specific systems, such as Taurus missiles.

The AfD, which opposes both aid to Kyiv and Ukraine’s aspirations for membership in the EU and NATO, has succeeded in attracting a broad spectrum of anti-Ukrainian sentiment from pro-Russian sympathizers, war-weary isolationists, and proponents of national egoism.

The AfD in power?

Despite its electoral gains, the prospect of the AfD attaining executive power at either the federal or state level remains unlikely — at least for now. The new Bundestag includes four factions in addition to the far-right party. Three of them — the SPD, Greens, and Die Linke — are ideologically incompatible with the AfD. Even the CDU/CSU bloc, which won the most seats in the February 2025 elections, has repeatedly ruled out any cooperation with the AfD. CDU leader Friedrich Merz has firmly rejected the idea of working with the far right, citing his own convictions, the will of his voters, the decisions of party leadership, and a resolution from the 2018 party congress. Just weeks before the February vote, Merz stated unequivocally: “We will not cooperate with the AfD. We will not tolerate it. There will be no minority government. Nothing.”

Still, not all members of the CDU share this uncompromising stance. Even during Merkel’s chancellorship, some figures from the party’s right wing argued for treating the AfD as a “normal conservative party” — opening the door to potential collaboration. In early 2025, the CDU branch in Harz (Saxony-Anhalt) cited poor regional performance and a wave of party defections as part of a letter urging the national leadership to abandon the so-called “brandmauer” (“firewall”) and consider coalition options involving the AfD.

A more weighty development came in April, when Jens Spahn — former health minister and soon-to-be head of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group — suggested treating the AfD like any other opposition party “in organizational matters.”

He was referring to committee chairmanships, which are allocated proportionally — though the AfD is entitled to several key posts, other parties have consistently voted against its candidates. After facing backlash from colleagues and media, Spahn walked back his remarks, saying they had been misunderstood and denying any intent to normalize relations with the far right. Still, such comments from a top-ten CDU figure were seen as a warning sign.

At present, it remains difficult to imagine Merz allowing any form of cooperation with the AfD. He has repeatedly stated his rejection of the far right’s ideology and his unwillingness to partner with them. Most CDU members and voters share Merz’s opposition to working with the AfD.

Ultimately, the future of German democracy may hinge on the new government’s performance. Should it fail to meet the country’s mounting challenges, the AfD stands to grow stronger — particularly by drawing in even more disappointed Merz supporters.

The AfD may also gain ground on the far-left flank. The much-anticipated political project of Sahra Wagenknecht fell short of expectations. Her namesake bloc failed to enter the Bundestag, and internal conflicts have erupted between her appointees and local leaders in states like Thuringia. Given that Wagenknecht, too, has employed anti-migrant rhetoric, the AfD could siphon off support from this disillusioned segment as well.

As a new German government prepares to administer the country, one thing is clear: the AfD’s current success is unlikely to be its last.

In Germany, the term “people’s party” (Volkspartei) is not simply applied to any party that attracts large segments of the electorate or secures a significant share of the vote. The defining features are a broad thematic platform and strong local roots. For instance, despite having participated twice in federal governments, the Greens are not considered a “people’s party.” This is due to two key factors: (a) their relatively narrow focus—primarily on environmental issues and human rights—and (b) their uneven presence across the country. In some regions, the Greens have no representation in local parliaments at all, and their local branches are small and politically marginal. The CDU and SPD have historically met the criteria of a “people’s party” on all these counts—and now, in eastern Germany, so does the AfD

All parliamentary parties in Germany have repeatedly emphasized their categorical refusal to cooperate with or form coalitions with the far right. This united stance is commonly referred to in Germany as the Brandmauer — literally translated as a “firewall.”