A new conflict is flaring up in Libya. On May 28, allies of Libyan National Army (LNA) leader Khalifa Haftar attempted to seize control over oil production facilities in the country. This seemingly domestic dispute is drawing in larger geopolitical players — on May 10, the Kremlin published photographs of Haftar’s visit to Moscow, where he met personally with Vladimir Putin. With the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, Libya has become a key country for the Kremlin in its effort to preserve a military presence in the Mediterranean and Africa. But Turkey now stands in Russia’s way. In the early years of Libya’s civil war, Turkish authorities backed the «pro-Western» Government of National Accord in Tripoli, while Haftar, who took control of the country's east, relied more on support from Egypt, the UAE, and Russia. But in spring 2025, an unexpected shift occurred: Turkey began actively forging direct ties with Haftar’s LNA, a traditional Kremlin ally. Moscow, in turn, has brought Belarus into the effort to counter Ankara’s move. But Turkey’s offers — investments and arms — may be far more attractive to Haftar than the ill-defined benefits of cooperation with Russia.

Content

Libya is the new Syria

The Libyan triangle

Moscow's waning power

“Belarusian naval power”

Divide cooperation areas and conquer

Stability in exchange for recognition

Will Turkey push Russia out of Libya?

Libya is the new Syria

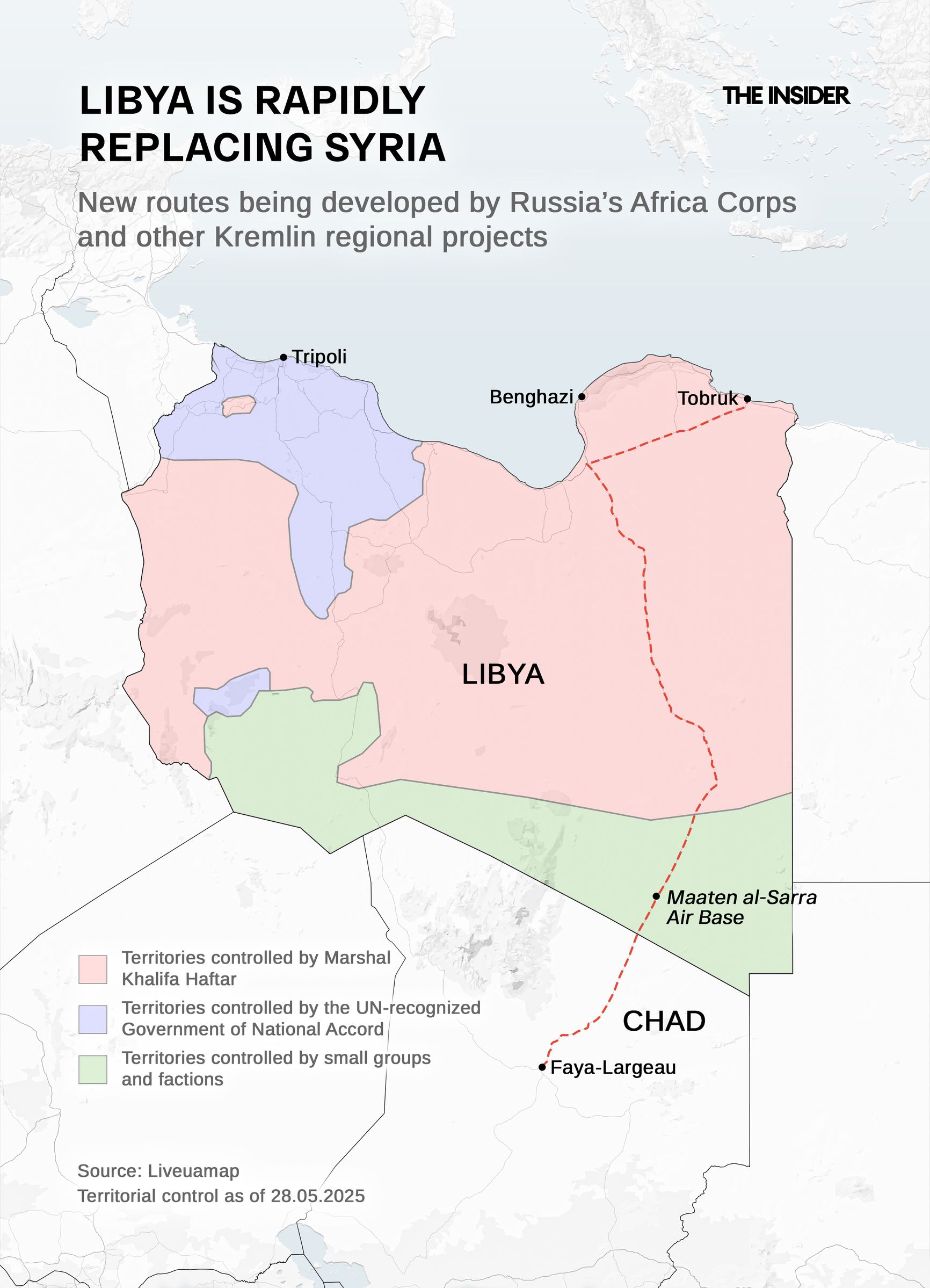

The fall of Damascus in December 2024 hit Moscow hard. Its continuing access to military objects in Syria — the naval base in Tartus and Khmeimim Air Base — were thrown into doubt, jeopardizing Russia’s presence in the Middle East. Libya, until then viewed merely as a backup airstrip, suddenly became the Kremlin’s primary stronghold in the region. Flights of Il-76 and An-124 military transport aircraft from Russian bases in Syria to Libya have increased markedly since December 2024. Meanwhile, heavy containers were unloaded at the Libyan port of Tobruk — under tight Russian military guard.

According to The Soufan Center, in the first quarter of 2025 the number of Russians stationed at just one Libyan air base — Brak al-Shati — increased from roughly 300 up to 450 people. Satellite imagery clearly shows a construction boom underway at Ma’aten al-Sarra air base in the south of the country near the border with Chad. Runways are being urgently restored, military hangars are going up, and new fuel and lubricant storage tanks are being laid. It’s clear that the facility is being prepared as a “long-range staging point” for operations in the Sahel, where Russia has established a presence — primarily in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

Libya is being prepared as a “long-range staging point” for Russian operations in the Sahel — namely Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger

At the same time, overland corridors from the coast into the continent's interior have come back to life. Columns of Russian military equipment and groups of instructors — including personnel from Russia’s newly created “African Corps” — are moving through Libya’s central regions, which are controlled by Haftar.

The Libyan triangle

Against this backdrop, the news broke that Turkey, a longtime vocal supporter of the Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli — Haftar’s opponents in the civil war — had abruptly shifted its approach. On April 4, 2025, Saddam Haftar, chief of staff of the LNA and son of Khalifa Haftar, unexpectedly arrived in Ankara.

It was immediately clear that this was no ceremonial visit. During the trip, the two sides signed a defense cooperation agreement covering key strategic areas from weapons deliveries (including modern drones) and military training programs to the development of military infrastructure and the provision of joint naval exercises on Libya’s eastern coast.

Saddam Haftar, son of eastern Libyan leader Khalifa Haftar

According to the Azerbaijani Telegram channel Bez Tormozov (“No Holds Barred”), Turkey plans to establish a military base in the southwestern Libyan city of Ghat, where a Turkish delegation has already inspected two airports. Moreover, amid strengthening bilateral ties, Turkish Airlines has resumed flights to Benghazi — a city under Haftar’s control — for the first time in ten years.

According to Jeune Afrique, the agreement is designed for the long term and includes 30 training programs for Libyan military personnel over the next five years, with a focus on drone operation and maintenance, engineering support (including demining), and other technical services. Joint exercises and the modernization of military infrastructure in eastern Libya are also under discussion as part of efforts to unify the country’s currently fragmented armed forces.

Turkey is investing money, supplying technology, and building infrastructure, while Haftar’s Libyan National Army grants Ankara exclusive access to its territories and military bases in the southwest of the country. In short, Turkey is now openly positioning itself as the LNA’s new patron, signaling a serious intent to gain a foothold in eastern Libya as a counterweight to Moscow. Like Russia, Turkey is gaining direct access to the Sahel. And Ankara’s “Libyan gambit” — sacrificing its previous ties with the GNA in order to rapidly expand its influence over the formerly pro-Russian LNA — is already bearing fruit.

A classic “love triangle” is taking shape: Moscow and Ankara remain geopolitical rivals while vying for the favor of the same Libyan general. Haftar, for his part, appears to be making a calculated move, seeking to gain greater autonomy by reducing his dependence on Moscow. For Russia, this is a deeply unpleasant surprise.

After losing Tartus, the Kremlin had serious plans to turn Tobruk into the main hub for its operations in Africa. Now, however, Erdoğan is not only partnering with the Kremlin’s Libyan ally — he is offering Haftar a far more attractive package. Putin, meanwhile, is unable to offer Haftar with what matters most: arms. Ever since Russia became bogged down in Ukraine, its own armored vehicles and modern weaponry have been in increasingly short supply, leaving it in no position to prop up its North African ally.

Moscow's waning power

In the past, Moscow provided Haftar with significant support. By early 2020, around 1,200 Wagner Group mercenaries were operating in Libya, carrying out a wide range of tasks — from guarding specific facilities to directly engaging in combat. By September of that year, according to estimates from AFRICOM (U.S. Africa Command), the number of Wagner mercenaries in the country had reached 2,000. However, Putin’s backing was not not enough to guarantee the victory of Haftar’s forces in the short term, and in the longer term, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would dramatically reduce the Kremlin’s capacity to provide material support to its allies abroad.

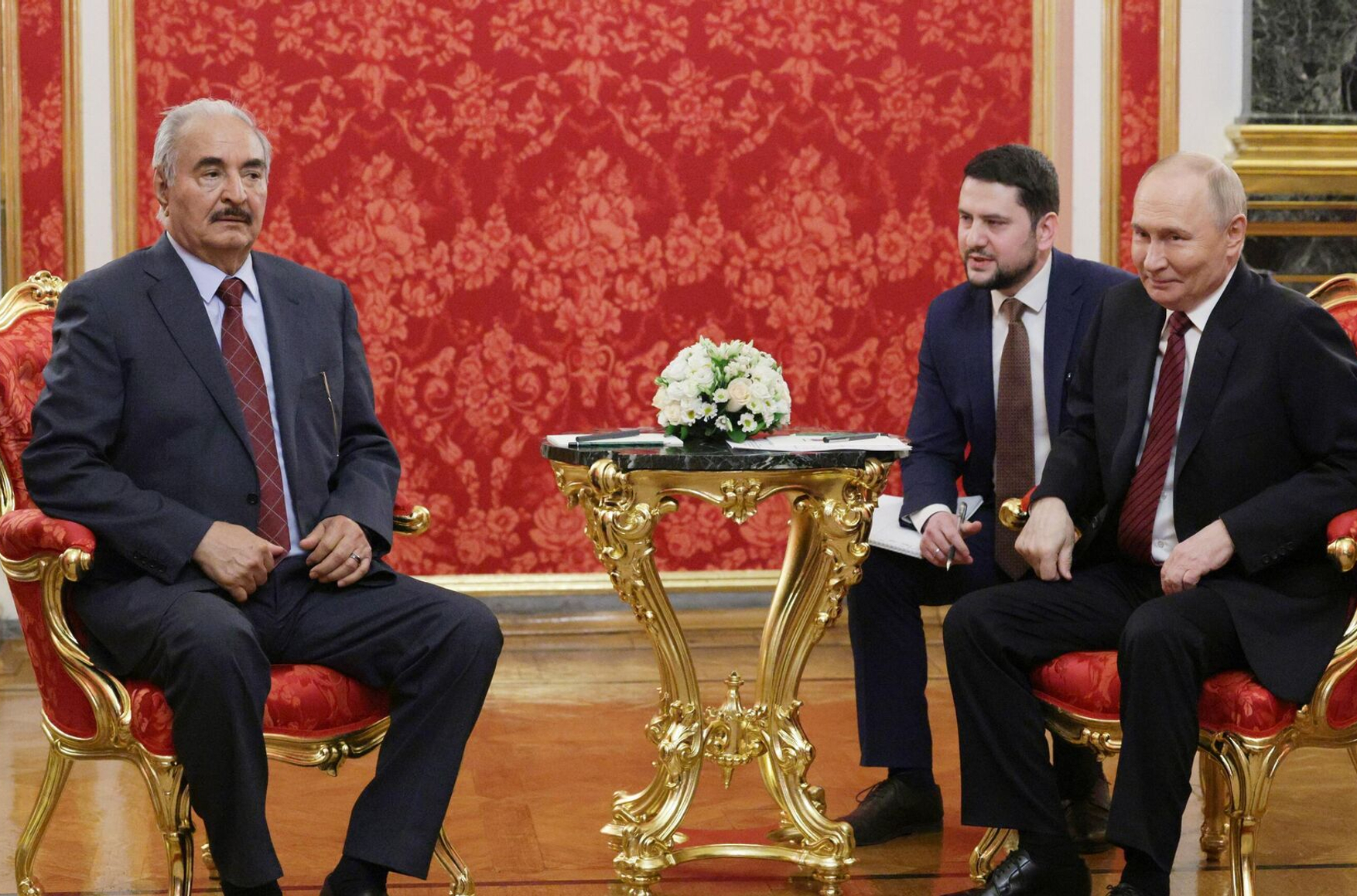

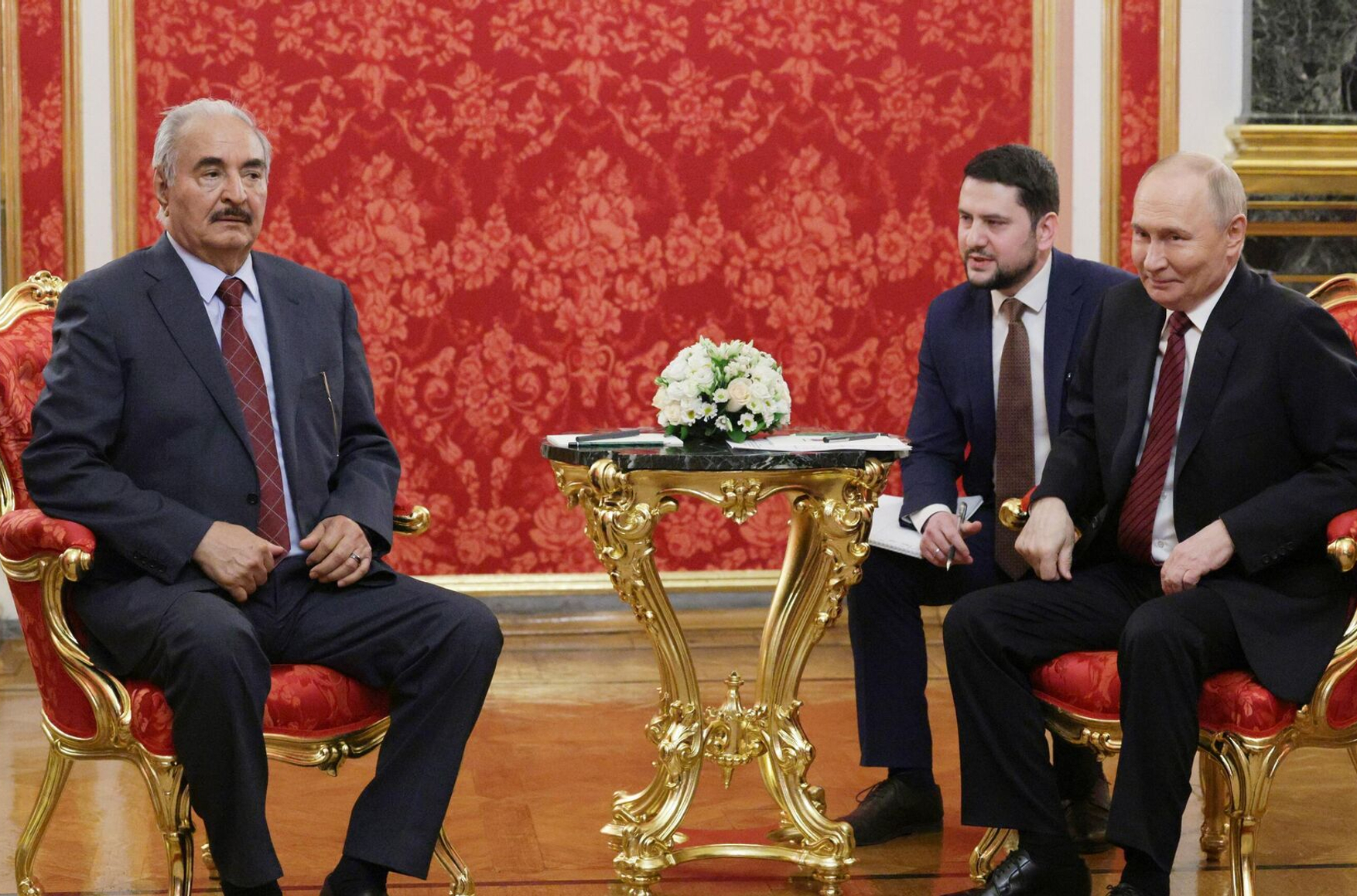

Khalifa Haftar with a delegation at talks in Moscow

Since 2022, Putin’s war in Ukraine has been burning through the Russian military’s stockpiles of materiel at a staggering pace. In the first month of the full-scale invasion, 1,300 Wagner fighters were urgently withdrawn from Libya via Syria and redeployed to the Ukrainian front. By the end of 2024, less than 1,000 Russian mercenaries remained in Libya. After the effective dismantling of the Wagner Group, they were formally reassigned to Russia’s Ministry of Defense and reorganized into what is now known as the “Africa Corps.”

As the war in Ukraine demanded ever greater attention from the Kremlin, and with Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Damascus guaranteeing Russia access to its bases in Syria, the Libyan front began to slide into the background. At times Libya even appeared to be a strategic burden. Haftar had proven incapable of taking full control of Libya. His offensive on Tripoli in 2019–2020 collapsed, and after that blow, he never fully recovered his strategic potential.

Among the population in eastern Libya — territory under Haftar’s control — frustration with his regime began to grow, and reliance on the Kremlin was not a viable option. In the Middle East it is well known that Russia has a tendency to abandon its allies when they no longer prove capable of maintaining domestic authority. For example, former Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir, who was deposed in 2019, is still sitting in prison in his home country awaiting extradition to the International Criminal Court. Another erstwhile Kremlin ally, former state minister of Nagorno-Karabakh Ruben Vardanyan, is currently in an Azerbaijani prison. While Ukraine’s Viktor Yanukovych (2014) and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad (2024) managed to escape to Russia before their own people could get ahold of them, there is no guarantee that Haftar could succeed in following their example.

“Belarusian naval power”

In a difficult situation, Russia found an unexpected helping hand in Libya from its ally Belarus. In February 2025, at Haftar’s initiative, an unprecedented tripartite protocol was signed in Minsk on the joint use of logistical support facilities belonging to the Libyan National Army (LNA). Officially, the document is an annex to the earlier memorandum on military-technical cooperation between Russia and the LNA. Unexpectedly, Belarus’s Ministry of Defense bypassed a mandatory ratification process in order to join the agreement.

Khalifa Haftar in Minsk

The pact is set to last for 25 years, with an option for automatic extension. It grants the allies access to 11.7 square kilometers of the inner waters of Tobruk’s port, along with the adjacent land area. Russia and Belarus also enjoy access to a wide range of port infrastructure within a ten-kilometer zone, including fuel depots, repair workshops, and UAV launch pads.

A source of The Insider’s who is familiar with the text of the agreement claims that Moscow also secured the right to station up to 1,200 personnel there — a force the size of a Navy logistics battalion — along with helicopters, drones, and air defense systems, while Minsk is allowed to deploy engineering specialists. There are also rumors about a battery of upgraded air-defense systems, namely of the Buk variety. Moscow assumed responsibility for reconstructing the northern breakwater and laying a main fiber-optic cable to the al-Abraq airbase, while Minsk is tasked with modernizing the port’s power station and installing a mobile dry dock.

In practice, Russia and Belarus now operate a joint command center in Libya, with part of the Kremlin’s operations being conducted “under Belarusian cover” as per an agreement with the country’s head-of-state Alexander Lukashenko. Service members from both Russia and Belarus are exempt from Libyan legal jurisdiction and taxation. UN observers are allowed inspection access no more than once a year and only with prior notification.

As a result, over the course of just a few months Libya has been transformed from a “backup airfield” into a full-fledged staging ground for projecting Russian military power into the central Mediterranean and the Sahel region of Africa.

Divide cooperation areas and conquer

Moscow’s efforts have not prevented Haftar from diversifying his foreign ties, which allows him to address several major strategic and geopolitical goals at once. Balancing between several patrons not only expands his room for maneuver, but also helps avoid overreliance — and thus pressure — from any single player. Such an approach serves as insurance in the event that a former ally shifts its policy.

It can never be fully ruled out that the Kremlin, in pursuit of its own short-term tactical interests, may change its priorities or even move toward direct rapprochement with Haftar’s rivals. Not to mention the possibility that a Kremlin frustrated by a series of major setbacks could start blaming Haftar for its failures in Libya and respond by acting directly against him. In this context, Haftar’s efforts to build ties with Ankara send a clear signal to Moscow that the LNA has foreign-policy alternatives and can therefore shield itself from any potential cut in Russian support

And of course, Haftar is still seeking to strengthen his position within Libya itself. By receiving support from both Russia and Turkey, he signals to rival domestic forces that he is not just a military leader, but also a crafty diplomat. This increases his leverage in any negotiations about the country’s future, meaning that the LNA is no longer entering talks in isolation, but is instead backed by at least two major outside powers — a far more effective way to force the government in Tripoli to take its demands seriously.

Stability in exchange for recognition

The turmoil has seriously alarmed Italy, the main European investor in Libya’s energy sector. In 2023, Italian energy company Eni and Libya’s National Oil Corporation signed an $8 billion agreement for gas production — 750 million cubic feet per day — over a 25-year period starting in 2026. For Rome, further instability in North Africa is clearly undesirable.

Eni and the National Oil Corporation of Libya signed an $8 billion agreement for 25 years of gas production

Europeans have also long feared the risk of a new wave of migration from Africa should the military and humanitarian situation worsen. According to Agenzia Nova, the share of migrants arriving in Italy after departing from Libya’s shores has increased over the past year. A possible LNA offensive on Tripoli could push tens of thousands more refugees toward Europe in a matter of weeks. In response, the Italian Navy quickly ramped up its surveillance efforts off of Libya’s coast, the coast guards of several Mediterranean countries are updating their protocols for countering the migration threat, and humanitarian NGOs are also mobilizing additional resources.

France, another traditionally active player in Libya, has adopted a wait-and-see approach. Total Energies, which is already involved in major oil and gas projects in the Ghadames and Sirte basins, is also interested in expanding production by exploring new fields. Like Italy, it has no interest in chaos in the region. Therefore, if Turkish military installations can guarantee the security of Libyan oil fields, then Paris will likely be willing to overlook Ankara’s growing influence there.

Key European capitals are clearly interested in supporting those forces in Libya that can ensure the security of energy production and curb illegal migration. And for now, the only player that appears ready and able to quickly and effectively fill this role is Turkey — which, through its agreements with Haftar, is seizing control of strategic areas in eastern Libya from Russia. Moscow, which has received merely modest results despite long pouring significant resources into these same territories, now risks finding itself operating under the shadow of Turkish flags — if it can maintain a present in Libya at all.

Will Turkey push Russia out of Libya?

Despite its bold declarations, Russia faces a slew of obstacles in its efforts to maintain a presence in Northern Africa. Scarce resources that could significantly strengthen Russia’s presence in Libya are currently being consumed in massive quantities in Ukraine. Transferring additional aircraft or armored vehicles to Africa now would come at the cost of critically weakening the offensive in the Donbas, and the Kremlin is clearly not prepared to make that trade.

Turkey, by contrast, is aggressively ramping up its efforts in Libya. Modern drones, engineering brigades, direct investments, and a growing portfolio of infrastructure contracts are providing Ankara with ever more leverage over what may soon be Russia’s former allies. Whereas Russia operates in Libya — as elsewhere — mainly through sluggish state institutions and corrupt military advisors, Turkey relies on far more efficient and transparent networks of private contractors, defense conglomerates, commercial firms, and sovereign funds. This enables Ankara to act much faster, more flexibly, and — most importantly — more effectively than its Russian competitors.

Strikingly, Turkey’s cooperation with Haftar is expanding not just in military terms but also economically. Turkish private companies are actively joining the postwar reconstruction of eastern Libya. In 2023–2024, firms from Turkey were already involved in rebuilding infrastructure in areas under LNA control — for instance, in the reconstruction of the cities of Derna and Benghazi. In the latter, a new major international-class stadium was built with Turkish participation.

In April 2025, the Development and Reconstruction Fund of eastern Libya, headed by Belgacem Haftar — another son of the field marshal — signed twelve contracts with Turkish companies for major construction projects in Benghazi, al-Bayda, Shahat, and Tobruk. Through such agreements, Ankara is winning over local elites and the public by delivering visible, practical benefits: investment, jobs, and rebuilt infrastructure.

Yet Russia’s presence in Libya remains visible, at least for now. Combat drones, air defense systems, and training centers in Sabha and Benghazi may still be enough to keep Haftar from making a decisive break with Moscow. But that relationship may no longer be sufficient to counter Turkey’s growing momentum.

The spring of 2025 is shaping up to be a geopolitical turning point in North Africa. With a blend of military and economic tools, Turkey has begun to push Russia out of its position as the Libyan National Army’s primary partner and ally. Preoccupied with the war in Ukraine and limited in its stockpile of resources, Moscow appears increasingly unable to resist Ankara’s advance. Turkey’s flexible strategy — based on investment, soft power, and balanced cooperation — is already proving more attractive to Haftar’s circle than Moscow’s narrow military support. And Haftar, by hedging between rival backers, is steadily expanding his own room for maneuver.

If the trend holds, eastern Libya could soon shift from being a Russian stronghold to a contested zone — and ultimately, to a bastion of Turkish influence. At that point, Putin may have to start looking for a new Tobruk. Or a new Haftar.