Ceasefire talks in Gaza resumed immediately after the end of hostilities between Iran and Israel. One might expect that now, with the main backer of the region’s several anti-Israeli terrorist groups weakened, negotiations would become easier. The problem, however, is that there is no agreement on the future of Gaza — not even among Palestinian factions themselves. As a result, neither Israel, nor its Arab neighbors, nor international organizations, nor the various Palestinian movements on the ground have a clear idea as to who should govern Palestinian territory after the removal of Hamas — if such a removal ever even occurs.

Content

Support for Palestinian statehood

Why do Jews and Arabs dispute Palestine?

The origins of the “two states” principle

When did the conflict between Arabs and Jews begin?

The lot of the Palestinian Arabs

Resolution options as of today

No consensus

Support for Palestinian statehood

At this stage, most members of the international community agree that the solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict must be based on the principle of “two states for two peoples,” which envisions the peaceful coexistence of the Jewish state of Israel and an Arab state of Palestine.

Currently, the State of Palestine is recognized by 147 of the UN’s 193 member states. And more have expressed interest in joining the list. Recognition was expected to be announced at the UN conference in New York this past June, but the event was postponed due to the war in Iran. Among those ready to recognize Palestine is Malta, while France and the United Kingdom remain undecided. Ahead of U.S. President Donald Trump’s May visit to the Gulf states, unofficial reports emerged suggesting that he, too, might announce recognition of Palestine on his own. However, that did not happen, and according to the Qatari outlet The Middle East Eye, Washington went so far as to warn Paris and London against unilaterally recognizing Palestine outside the framework of a negotiated Israeli-Palestinian settlement.

On June 10, U.S. Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee told Bloomberg that Washington had lost its once firm belief that the Middle East conflict could be resolved through the “two states for two peoples” formula. When asked whether the creation of a Palestinian state remained a goal of U.S. policy in the region, he replied: “I don’t think so.” In any case, the Trump administration’s position remains highly inconsistent.

When asked whether the creation of a Palestinian state remained a goal of U.S. policy in the region, U.S. Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee replied: “I don’t think so”

Despite America’s opposition, several countries may soon be prepared to proceed with unilateral recognition of the Palestinian state. Hamish Falconer, the UK’s Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Middle East, told members of Parliament in early June that London’s position is shifting, and the lack of progress in peace talks is a key reason why.

“One reason that the traditional position of the UK government has been that the recognition of a Palestinian state should come at the end, or during, a two-state solution process was the hope that we would move towards a two-state solution,” Falconer told The Guardian, who explained that London’s thinking was partly influenced by rhetoric from some members of the Israeli government who have indicated that they are no longer committed to a two-state solution.

But before it seriously considers recognizing the State of Palestine, London wants guarantees that Hamas will be excluded from the governance formula in the Gaza Strip. France holds a similar position, and the Arab countries that have weighed in on the matter also agree that the terrorist group must go. Hamas, for its part, has stated its readiness to return authority in the Strip to the official Palestinian leadership — the Palestinian National Authority, headed by Mahmoud Abbas.

However, many questions remain about the fate of the armed forces of Hamas and other groups that do not recognize Israel. Some experts warn that by recognizing the State of Palestine, the EU risks endorsing the existence of multiple terrorist organizations linked to the Palestinian cause, as well as further corruption within the Palestinian Authority.

By recognizing the State of Palestine, the EU also risks endorsing the existence of multiple terrorist organizations

However, many experts and opinion leaders believe that recognizing Palestine is justified, despite all of the complexities — Israel’s unwillingness to cooperate with the Palestinian Authority prominent among them. Without such cooperation, a Palestinian state is unlikely to be viable.

Currently, the Palestinians receive electricity and water from Israel, use the Israeli shekel as currency, and move their exports and imports through Israeli territory. Moreover, the Palestinian territories are fragmented: the Gaza Strip is separated from the West Bank, and even within the West Bank, some areas are disconnected from others, with Arab communities interspersed among Israeli settlements.

Those who support recognizing Palestine see the provision of official diplomatic status as a way to pressure Israel and challenge its policies. Moreover, the more countries recognize the State of Palestine, the more agency and legitimacy it obtains on the international stage. Recognition also allows Palestine to open embassies, sign bilateral agreements, and participate in international forums.

The UN General Assembly took note of the proclamation of the State of Palestine back in 1988, when the Palestinian National Council declared independence at a session in Algiers.. Back then, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council — the Soviet Union and China — recognized Palestine. But things have been changing.

In 2012, Palestine was granted non-member observer state status at the United Nations. In April 2015, it joined the International Criminal Court (ICC) and brought forward allegations of war crimes committed by Israel in areas under the control of the Palestinian Authority, as well as accusations of occupation. In February 2021, the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber ruled by majority that the Court has jurisdiction to investigate the situation in Palestine — specifically in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza.

In May 2024, a UN General Assembly resolution granted the Palestinian delegation additional rights, including access to meetings and committees of UN member states, along with the right to propose agenda items. The only thing the Palestinians still lack in the UN system is the right to vote.

Why do Jews and Arabs dispute Palestine?

For centuries, the term “Palestine” has referred to a territory with shifting and often unclear borders. The word has ancient Hebrew origins and was originally pronounced as ‘Peleset.’ In the late second millennium BCE, the Jews used the term to describe a narrow strip of land along the Mediterranean coast — from what is now the Israeli city of Ashdod down to Gaza — inhabited by the Philistines (Pulasti).

The Hebrew word Peleset gave birth to the Greek term Palaestina, which was later adapted into Latin. In 135 CE, following the Jewish revolt led by Simon Bar Kokhba, the Roman Emperor Hadrian ordered that the name “Syria Palaestina” (Syrian Palestine) be applied not just to the coastal areas, but to the entire territory of the Roman province of Judea, which had replaced the ancient Kingdom of Judah.

After the Arab conquest of the territory in the mid-7th century, the Arabic version of the word Palestine — “Filastin” — came into use, referring to an administrative unit within various states ranging from the Umayyad Caliphate to the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, the boundaries of the territory designated as Palestine continued to change under the Roman and the Byzantine Empires. In Christian tradition, the word “Palestine” has been and remains synonymous with the term “Holy Land.”

During World War I, British representatives made promises to both Arabs and Jews in order to secure their support in the war against the Ottoman Empire.

In 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour promised in a letter to Lord Walter Rothschild, a representative of the British Jewish community, to establish a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. The reference was to the “Land of Israel,” not to a specific administrative unit. This letter became known as the “Balfour Declaration,” and it later served as the basis for the creation of a Jewish state. For the Arabs, it marked the starting point of the conflict with Israel.

The “Balfour Declaration” became the foundation for the creation of a Jewish state and, for the Arabs, the starting point of the conflict with Israel

It is far less commonly known that in 1915-1916, British High Commissioner in Egypt Sir Henry McMahon exchanged a series of letters with Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the King of the Hejaz and custodian of the holy sites in Mecca and Medina under Ottoman rule.

The letters discussed the conditions under which Sharif Hussein would support an Arab revolt against the Turks, and in order to secure his assistance, London promised to appoint Hussein king of a new Arab state. Sharif Hussein sought control over the Arabian Peninsula (excluding the port of Aden in Yemen), Iraq, Syria (including Lebanon), and Palestine. Britain delineated its boundaries thusly: “The districts of Mersina and Alexandretta [today Mersin and Iskenderun in eastern Turkey] and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded.” Many Arabs see this passage as proof that Palestine was promised to them prior to the publication of the Balfour Declaration.

In 1920, following the end of World War I and the division of the Ottoman Empire’s territories, Britain was granted a mandate to govern Palestine, with directives for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in the region. The mandate covered land on both sides of the Jordan River and was approved by the League of Nations in 1922.

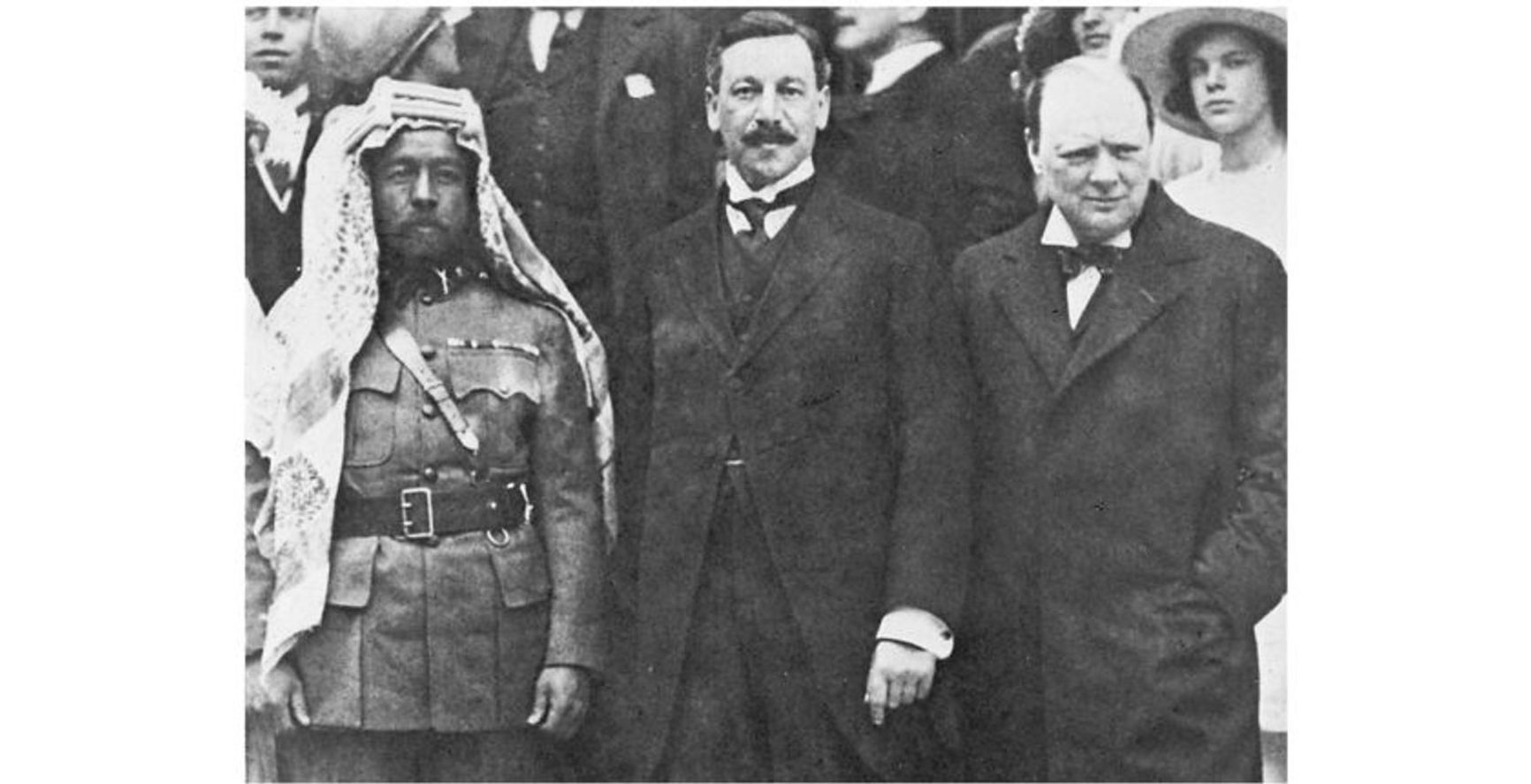

Winston Churchill in Jerusalem, 1921

However, a year earlier, Britain’s Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill had decided to allocate three-quarters of the Mandate territory to a separate Arab emirate — Transjordan. The first emir was the son of Sharif Hussein — Abdullah, who in 1946 became the first king of Transjordan when the emirate gained independence. After the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, the country’s name was changed to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, and its territory expanded. Given the history of the kingdom’s formation, some circles in Israel argue that an Arab state already exists on the territory of Palestine — and that it is Jordan.

The origins of the “two states” principle

The foundation of the “two-state” vision was set down in a UN General Assembly resolution adopted on November 29, 1947, which called for the creation of two states on the territory of British-mandated Palestine — one Jewish and one Arab. According to the proposed maps, the borders of both states were initially fragmented, and Jerusalem was to become an international city. Thirty-three countries, including the Soviet Union and the U.S., supported the plan; 13 countries voted against it; and 10, including the UK, abstained. Nevertheless, London promised to withdraw its troops by August 1948. It ultimately did so three months earlier, on May 14.

The Jewish community of British-mandated Palestine accepted the UN plan, and immediately after the British withdrawal, the independence of the State of Israel was proclaimed.

© AFP 2024 / Intercontinentale

Arab politicians — both within British-mandated Palestine and beyond — rejected the partition. They were fundamentally unwilling to accept the existence of a Jewish state and vowed to destroy it. It took several wars before it became clear that Israel would not disappear from the political map.

When did the conflict between Arabs and Jews begin?

The UN resolution resulted from several decades of conflict between the Arab and Jewish populations of Palestine. Its roots go back to the late 19th century, when pogroms in the Russian Empire triggered a wave of Jewish immigration to Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel), which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. It was also at that time that the Jewish national movement, known as Zionism, emerged.

The word, which first appeared in 1890, unites a group of people who strive to ensure the return of the Jewish people to Eretz Israel through political means. The term derives from the toponym Zion, which in the books of the Jewish prophets was used to denote Jerusalem. For the Jewish diaspora, it became a symbol of the lost homeland.

In 1896, the future founder of the World Zionist Organization, Theodor Herzl, published a pamphlet entitled Der Judenstaat: Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage (The Jewish State: An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question). A year later, the First Zionist Congress in Basel defined the movement’s goal: to establish a legally guaranteed homeland for the Jewish people in Eretz Israel.

Palestinian Arabs staged the first anti-Zionist protest on February 27, 1920, after the League of Nations announced its approval of the Balfour Declaration. Pogroms in Jerusalem and other cities continued for four days and led to a further escalation in tensions. In the late 1920s, Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam formed an underground militant group in Haifa and began recruiting Arab peasants to create clandestine cells aimed at fighting the British mandate and the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine). Today, Hamas’s military wing is named after the sheikh.

The first anti-Zionist protests in Palestine began on February 27, 1920, following the approval of the Balfour Declaration as the basis for a “national home for the Jewish people.”

Arabs protested against Jewish immigration, accusing Jews of fueling unemployment — an issue exacerbated by the overall economic situation in Palestine and beyond. However, some historical studies note that Jewish immigration and the related economic changes were not a curse but a benefit for the local Arabs. According to the data, Jewish enterprises employed about 12,000 Arabs, contributing to the intensive development of Mandatory Palestine.

The local economy grew at an average annual rate of 4.5% (lower than in the Jewish sector but higher than in neighboring Arab countries), peaking in the early 1930s. Nevertheless, the Arabs believed that the Balfour Declaration deprived them of their right to self-determination (even though they were the majority at the time) and saw Jewish immigration as a form of colonialism. As a result, a large-scale Arab uprising broke out in the mid-1930s, led by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammed Amin al-Husseini.

The uprising fell short of its goals, but modern Arab historians believe it facilitated the “birth of Palestinian Arab self-identity.” Similar processes were underway in other regions of the former Ottoman Empire, where modern states were emerging in areas with noticeably heterogeneous ethno-religious composition.

In the meantime, the Western powers did not always take demographics into account when drawing the borders of future countries, which led to the division of national groups including the Kurds, Druze, and Bedouins. This primarily affected Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and the Palestinians. Later on, it led to numerous regional conflicts, many of which continue to this day. The hostilities in Syria ongoing since 2011 are one of the most vivid examples.

Western powers did not take demographics into account when drawing the borders of future countries

The next stage in the formation of the Palestinian nation came in the 1960s, when the Arab League decided to create the Palestine Liberation Organization. The PLO brought together a range of Palestinian groups that were willing to wage a war of terror against Israel and Jewish citizens worldwide.

The lot of the Palestinian Arabs

The Arabs living in the British Mandate territory of Palestine were initially divided between Transjordan and the remaining part of the mandate. The first Arab-Israeli war in 1948 complicated their status even further.

As a result of the war, Jerusalem was divided between Israel and Jordan, which also occupied the territory of the West Bank of the Jordan River (known in Israel as Judea and Samaria), while Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip.

This war also gave rise to the problem of Palestinian refugees. According to the UN definition, they are the people who lived in Palestine between June 1, 1946, and May 15, 1948, and who lost their homes and livelihoods as a result of the 1948 conflict.

Later, this group came to include Arabs who fled their homes as a result of the 1967 Six-Day War. During that conflict, Israel captured the entire Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), and the Golan Heights. Jewish settlements began to be built on the annexed territories. The state authorized and encouraged this practice, both as part of establishing security outposts and as a means of creating “facts on the ground.”

Government Press Office/REUTERS

In 1950, when the UN established the agency for Palestinian refugees — the United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA) — their number stood at about 750,000 people. Today, according to UNRWA, 5.9 million Palestinian refugees are eligible for assistance. Almost one-third of them — more than 1.5 million people — live in 58 camps specifically created for them in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. The rest have dispersed around the world, but no Arab country other than Jordan has granted Palestinians citizenship, choosing instead to hold onto the refugee issue as a form of leverage against Israel.

After the 1967 war, Jordan and Egypt abandoned the Palestinians living in the territories occupied by Israel, even though between 1948 and 1967 they had been responsible for their fate. UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 treat the territories captured by Israel in 1967 as occupied. With some conditions, they are expected to become part of a future Palestinian state. The Golan Heights are to be returned to Syria. As for the Sinai Peninsula, Israel returned it to Egypt under the peace treaty signed between the two countries in 1979.

The treaty was based on framework agreements between Israel and Egypt, and it pioneered the idea of autonomy for Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza. This autonomy was intended to result from negotiations between Israel, Jordan, and Egypt.

A transitional period of five years was envisioned, during which a self-governing authority would be elected, followed by negotiations on the final status of the territories — including on the issues of Jerusalem, borders, refugees, and Israeli settlements. However, this plan was not implemented in any form until 1993, when the Oslo Accords were signed. Egypt and Jordan were excluded from this process. For the first time, the Palestinians — represented by the PLO — conducted the negotiations independently.

At the time, the PLO recognized Israel’s right to exist and renounced terrorism. In turn, Israel recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. Based on the accords, the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was established. The transitional period began with the transfer of Jericho and the Gaza Strip — excluding existing Israeli settlements — to Palestinian administrative control.

PLO leader Yasser Arafat, King Hussein of Jordan, U.S. President Bill Clinton, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, 1996

AP Photo/Joe Marquette

The second interim agreement between the PLO and Israel was signed in Washington on September 28, 1995, and it divided the West Bank into three areas. Area A, which included all cities except Hebron, was placed under full Palestinian civil and security control. In 2005, after the evacuation of Israeli settlements from Gaza, the entire Gaza Strip became Area A. Hebron was divided into Areas A and B in 1997.

Area B, which included smaller towns and villages, was placed under Palestinian civil control but remained under Israeli military control. Area C, which comprised dozens of Palestinian villages, remained under partial civil and full military control of Israel. Jewish settlements and military infrastructure in the West Bank were granted special status within Area C.

As for Jerusalem, in 1980 the Israeli Knesset passed a law declaring the city the unified and indivisible capital of Israel. Arab residents of East Jerusalem hold a special status — that of permanent residents of Israel. They have the right to live and work in Israel, to access the state’s healthcare and education systems, and to vote in municipal elections (though not in Knesset elections). This residency status can be revoked if a person lives outside the city for an extended period or obtains another citizenship.

An attempt to reach a final agreement was made in 2000 at Camp David, and a second try was made in 2001 in Taba — at the height of the Second Intifada. On these occasions and after, various proposals were put forward for dividing the territory and resolving the refugee issue, but no compromise was reached. The Israeli side was willing to make significant territorial concessions, but the Palestinians rejected the offers.

The issues that caused the fiercest debate were the refugees’ right of return and recognition of Israel as a Jewish state, albeit with a sizable Arab population (21%). In Israel, there is great fear that demographic growth will enable the Arab population to dominate and dilute the Jewish character of the country. Another contentious issue is the fate of Jerusalem.

In Israel, there is great fear that the Arab population to become dominant through demographic growth

In 2005, Israel evacuated all the settlements it had established in the Gaza Strip and withdrew its troops from the area. In 2006, Hamas won the elections to the Palestinian National Council, and a year later the group forcibly took control of Gaza. Many representatives of the official administration and Fatah (the main party behind the PLO and PNA) were captured, executed, or expelled from Gaza. Since 2014, no negotiations have been held between Israelis and Palestinians. Now, in the second year of the war that began after the October 7 attacks, Hamas has declared its readiness to return Gaza to the control of the Palestinian Authority, but at the same time, it refuses to lay down its arms.

Resolution options as of today

Currently, the following scenarios for Gaza’s future are on the table:

- Israeli military and civil control over the Gaza Strip — in other words, a temporary occupation of Gaza. This option makes any negotiations on the Israeli-Palestinian settlement impossible.

- Hamas remaining in power in Gaza — another dealbreaker.

- The return of the Palestinian National Authority to Gaza under the supervision of the U.S., the EU, and various Arab states, who will all assist in restoring security and rebuilding the Gaza Strip after the war. While this scenario is preferable for the majority of the international community, it implies the disarmament of Hamas and the inclusion of Gaza’s situation in the broader context of a final Israeli-Palestinian settlement based on the “two-state solution.” This returns us to the question of each side’s openness to dialogue.

- For the Israeli authorities, the most acceptable option at present is to retain security control over Gaza while transferring all administrative matters to local governing bodies not affiliated with Hamas. These could be clan-based groups or factions willing to cooperate with Israel. One example is the group led by Yasser Abu Shabab. However, due to his questionable reputation and accusations of smuggling and drug trafficking, this option raises many concerns and also excludes a comprehensive resolution of the conflict — meaning the situation on the ground would essentially remain unchanged.

For now, the agenda includes a renewed ceasefire in the Gaza Strip for 60 days. As Israel Hayom reported at the end of June, Trump and Netanyahu have agreed on a new “strategic plan” based on the following principles:

- The war in Gaza shall end within two weeks. The terms for ending the conflict shall include the arrival of four Arab countries (including Egypt and the UAE) to govern the Gaza Strip instead of Hamas. The remaining Hamas leaders shall be deported to other countries, and the hostages shall be released.

- Several countries around the world will accept Gaza residents who wish to emigrate.

- The Abraham Accords shall be expanded: Syria, Saudi Arabia, and other Arab and Muslim countries shall recognize Israel and establish official relations with it.

- Israel shall express readiness for a future resolution of the conflict with the Palestinians in line with the “two-state” concept, provided that reforms are carried out in the Palestinian Authority.

- The U.S. shall recognize the application of a certain extent of Israeli sovereignty in Judea and Samaria.

These clauses closely resemble Trump’s “Deal of the Century” — the peace plan he offered to the Palestinians and Israelis in 2020, only to face categorical rejection from the Palestinian side.

There is no telling how a similar plan would be received today, but so far, no reports about a possible ceasefire deal have mentioned deporting Hamas.

No consensus

For both Israeli authorities and the majority of the population — primarily the Jewish community — the question of creating a Palestinian State is not on the agenda. The prevailing attitude toward this scenario is mostly negative.

One of the main reasons is the refusal to allow Palestinian independence to be granted as a reward for the terrorist attack that Hamas and other groups perpetrated on October 7, killing 1,200 civilians and taking hundreds of hostages. Moreover, the discussion about the Palestinian state and its borders could potentially further divide Israeli society, which is already torn by internal problems. The terror of the 1990s following the Oslo Accords, the second Intifada that erupted in 2000, Hamas’s takeover of the Gaza Strip, and, finally, the October 7 attack have caused most Israelis to become resentful of any potential compromises with the Palestinians.

“The public believes that political agreements will not improve the country’s security and that the establishment of a Palestinian state poses a clear threat to Israel” — such was the conclusion drawn from two rounds of focus groups conducted in 2024 by the Israeli Institute for National Security Studies (INSS).

Furthermore, participants in the study said that Israel should rely solely on military force to protect itself, and that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has no solution. Moreover, they perceive the creation of a Palestinian state in Judea and Samaria as a direct threat to Israel’s security and a reward for terrorism. Regarding Gaza, the majority of respondents believe that Israel should maintain control over the Strip in order to prevent Hamas from rebuilding its military strength.

Other studies paint a similar picture. According to a Pew Research Center poll conducted in February–March 2025 among 998 adult Israelis, only 21% of respondents believe that Israel and a Palestinian state can coexist peacefully. This is the lowest figure since 2013, when the Pew Research Center began asking the question. Three-quarters of those surveyed cite the lack of trust between Israelis and Palestinians as the main obstacle to peace. The status of Jerusalem and Jewish settlements in Judea and Samaria also remains a problem.

However, much depends on the context and the framing. According to a joint survey conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR) in Ramallah and the International Program on Conflict Resolution and Mediation at Tel Aviv University in July 2024, when asked to choose between a regional war or a regional peace agreement that includes the Israeli-Palestinian two-state solution and Arab-Israeli normalization, 65% of Palestinians and 62% of Israelis chose peace (combining those who answered “maybe peace” and “definitely peace”). Meanwhile, 29% of Palestinians and 38% of Israelis prefer regional war (also combining “maybe” and “definitely” responses). Differences between Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were minimal. Among Israeli citizens, 55% of Jews and 89% of Arabs prefer peace over war.

Slightly different figures appear in the same survey when respondents are asked specifically: “Do you support a solution based on the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel, known as the two-state solution?” Forty percent of Palestinians answered positively to this question (an increase of 7 points compared to a pre-war survey in 2022). Moreover, the opinions of residents of the West Bank and Gaza Strip differ little: 39% and 42%, respectively. In May 2025, a separate survey by the same center showed that overall Palestinian support remained at 40%, but the gap between West Bank and Gaza residents widened and reversed: 45% and 39%, respectively.

In Israel, the situation is more complicated. Overall, 31% of respondents said “yes.” But among the Jewish community, only 21% responded affirmatively (a drop of 13 points since 2022 and the lowest level since similar questions were first asked in the early 1990s). Meanwhile, among Arabs who are Israeli citizens, support stands at 72%.

In Israel, only 21% of Jews — and more than 72% of Arab citizens — support the creation of a neighboring Palestinian state

The survey also considers other possible paths toward resolving the conflict.

— A confederation of two states, in which citizens of one country are allowed to live as permanent residents on the territory of the other, but each national group votes only in its own state’s elections. The provision of freedom of movement for all (with necessary security measures). Jerusalem will not be divided, but will become the capital of both states. Israel and Palestine will jointly handle security and economic matters.

This option is supported by 35% of Palestinians (up from 22%) and 20% of all Israelis (compared to 29% in 2022). Among Israeli citizens, 12% of Jews and 52% of Arabs support the confederation solution; among Palestinian Arabs, support stands at 28% in the West Bank and 45% in Gaza.

— A single Palestinian state with limited rights for Jews (supported by 33% of Palestinians) or a single democratic state with equal rights for all (this option is supported by 25% of Palestinians and 14% of Israeli Jews).

— Annexation of the West Bank without equal rights for Palestinians (supported by 42% of Israeli Jews).

Overall, the results of various polls demonstrate that support for the “two states for two peoples” solution fluctuates depending on the proposed terms of implementation. Primarily, this concerns the territories involved, the significance of deviation from the 1967 borders, and in whose favor they will be made. However, when it comes to Palestinians currently living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, there are no significant differences on this issue. For them, the key factor is more likely the feasibility of establishing a Palestinian state.

In May 2025, 64% of Palestinians believed that the two-state solution was no longer practical due to the expansion of Jewish settlements, while 33% believed it could still work. In Israel, opinions vary sharply depending on community affiliation, but the government primarily focuses on Jewish voters.

Undoubtedly, public opinion is influenced by politicians and heavily depends on current events. But for now, the ground for negotiations remains very fragile. The alternatives mentioned in the surveys — such as a confederation of Palestine and Israel (and sometimes even Palestine, Israel, and Jordan) or the creation of a single state — are also quite doubtful in terms of feasibility.

One can debate why the peace process has repeatedly failed: whether extremists on both sides are to blame, whether there was any political will for compromise among Palestinian and Israeli leaders to begin with, or whether both sides were too busy trying to keep the upper hand. But these discussions do nothing to bring resolution any closer — or even refute those who see the conflict as fundamentally unsolvable. Whatever the case, one thing is certain: the issue will not be resolved simply by the fact that a growing number of countries and international organizations are moving towards recognition of the State of Palestine.