Photo: Zelenskiy / Official / Telegram

Photo: Zelenskiy / Official / Telegram

Following recent talks in Berlin between representatives from Washington, Kyiv, and the EU, Vladimir Putin again said his demands for ending Russia’s war against Ukraine had not changed. He continues to insist on full control of Donbas, arguing that Russia will eventually seize the territory even as Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky records video messages in cities Moscow claims to have captured. For Ukraine, a voluntary withdrawal from the Donbas is unacceptable, as it would endanger the entire half of the country located east of the Dnipro River. The issue of future funding for Ukraine’s armed forces and postwar reconstruction also remains unresolved, and the potential use of frozen Russian assets remains a topic of heated debate. Under a working proposal, those assets would serve only as symbolic collateral for a €90 billion loan agreed to by EU leaders. Perhaps the most pressing question, however, is what Western security guarantees should look like. Any measures must be strong enough to prevent renewed aggression while also leaving no room for the Kremlin to use them as a pretext for future escalation.

The evolution of the “peace plans”

Withdrawal of Ukrainian troops from the Donetsk Region

Limits on the size of Ukraine’s armed forces

Security guarantees for Ukraine

What does this mean in the end?

The first version of a 28-point peace plan for Ukraine, informally labeled an “American proposal,” appeared in media reports on Nov. 20. It later emerged that the document was a lightly edited set of provisions that had largely been formulated by Kirill Dmitriev, Moscow’s envoy for talks with the United States, and Yuri Ushakov, a foreign policy aide to Putin. The Russian side passed its version of the document to U.S. presidential envoy Steve Witkoff, and the resulting Witkoff-Dmitriev plan contained nearly all of the Kremlin’s maximalist demands that Ukraine had already repeatedly rejected.

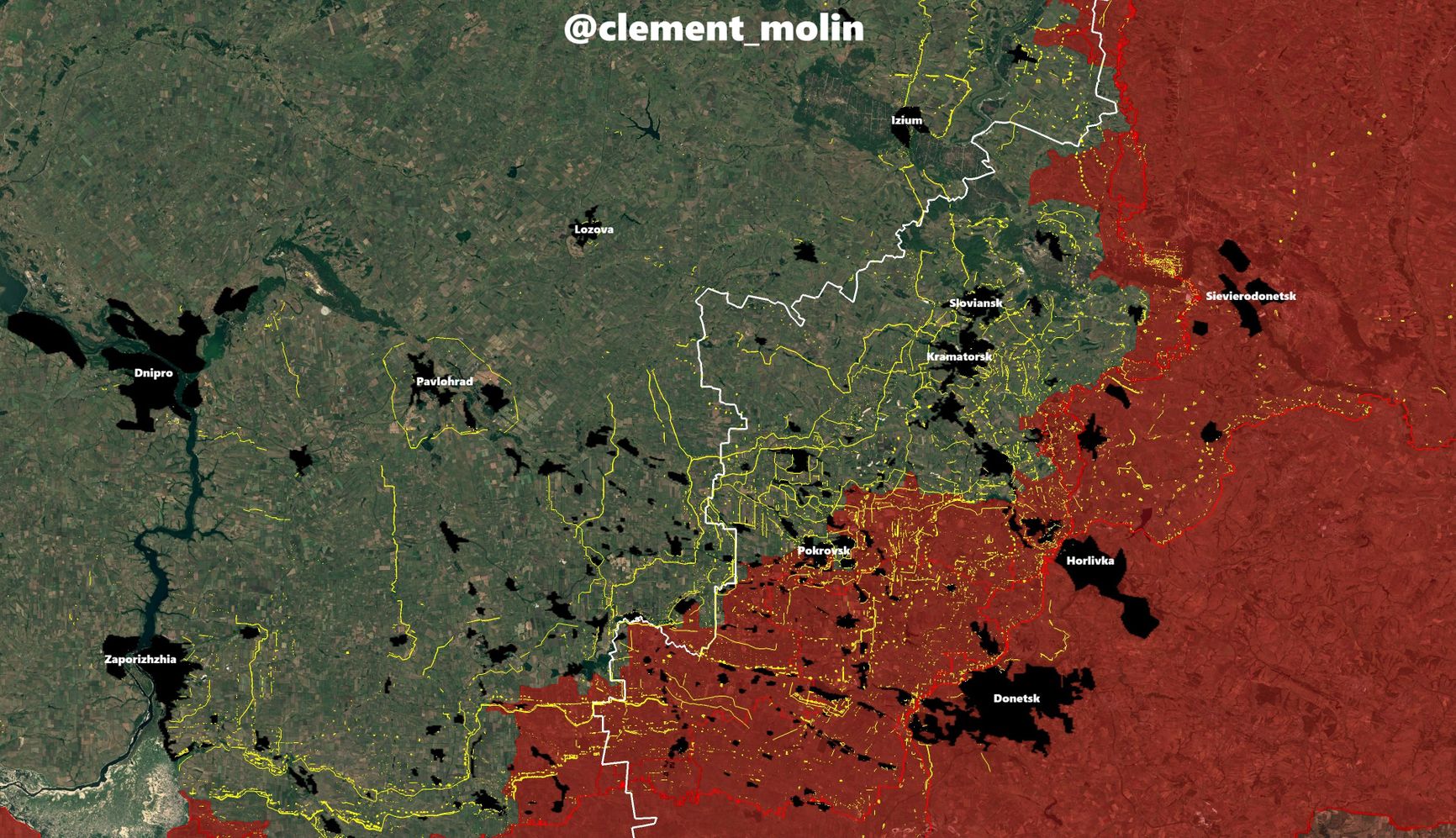

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

A newer 20-point version of a plan to end the war, published in Ukrainian media, differs somewhat from the earlier proposal. It was discussed in Berlin on Dec. 14-15 during meetings between Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner and Witkoff, along with European officials and Zelensky. The Russian side has expressed no willingness to consider the revised version.

The central question in the talks is the line at which both sides would be prepared to stop fighting. Russia’s position remains unchanged: full control of the Donbas. Although the Luhansk Region is almost entirely occupied by Russian forces, such terms would still require Ukrainian forces to withdraw — without a fight — from the significant parts of the Donetsk Region that remain under Kyiv’s control.

The Insider has previously detailed why surrendering the remaining part of the Donbas — including a belt of heavily fortified “fortress cities” that are integrated into a broader defensive line in eastern Ukraine — would pose a direct threat to the security of the country’s entire “left bank” east of the Dnipro River.

Under the Dmitriev-Witkoff plan, the abandoned territories would become a “demilitarized zone.” The proposal also included demands for the recognition of Crimea — and, implicitly, Sevastopol — as well as the acceptance of “de facto” Russian control over Donetsk and Luhansk and a freezing of the front line in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

In effect, the proposal preserves a “trade-off”: Ukraine would relinquish the remaining areas of the Donetsk Region under its control in exchange for Russia halting its offensive in Zaporizhzhia Region, abandoning its attempts to attack Kherson, and withdrawing its forces from regions not formally incorporated into Russia’s constitution — Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, Sumy, and likely Mykolaiv. As a concession, the vacated areas of the Donetsk Region would be designated a “demilitarized zone” with no Russian or Ukrainian forces.

But Moscow’s interpretation of demilitarization is highly specific and unlikely to be acceptable to Kyiv. Comments by Ushakov have made it clear that the Kremlin intends to deploy units of the National Guard, or Rosgvardiya, and police forces there — effectively handing the territory to Russia’s security agencies, rather than to the military.

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

If Russia’s National Guard enters parts of the Donetsk Region left by the Armed Forces of Ukraine, that will not amount to “demilitarization.”

After Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny in June 2023, Rosgvardiya was granted the right to possess heavy weapons. Some units have already received tanks, artillery, and mortars. The force also formally includes numerous Chechen security units that took part in the early stages of the full-scale invasion. In practice, the presence of Rosgvardiya in a “demilitarized zone” in the Donbas would resemble the situation that existed from 2015-2022 under the Minsk agreements, when so-called “people’s militias” operated in separatist-held parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

According to the DeepState mapping project, since the start of 2025 Russian forces have captured about 2,500 square kilometers in the Donetsk Region, but more than 22% of the territory remains under Ukrainian control. Even at the current Russian rate of advance, analysts estimate it would take Moscow’s forces roughly three more years to seize the region entirely (assuming the nature of the fighting does not change dramatically and Ukraine’s army and state remain resilient). As time is the key resource in a war of attrition, a decision by Ukraine to abandon positions that would take the enemy three years of exhausting combat to conquer seems like an irrational price to pay for the promise of a vaguely defined “demilitarized zone.”

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

Even at the current Russian rate of advance, it would take Moscow’s forces roughly three more years to seize the region entirely.

Separate concerns are raised by provisions calling for recognition of Russian sovereignty over Ukrainian territories currently under Russian control. In the proposed form, such recognition appears legally unworkable and directly contradicts international law.

All known versions of peace plan proposals include provisions to cap the size of Ukraine’s military. Under the Witkoff-Dmitriev plan, the ceiling is set at 600,000 troops, while the 20-point plan proposes a limit of 800,000 — roughly matching the current size of Ukraine’s Armed Forces, though not the broader Defense Forces of Ukraine, which also include units of the National Guard, National Police, State Border Guard Service, military intelligence (HUR) and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

Before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s army numbered just under 200,000. During talks in Istanbul in the spring of 2022, Russia demanded that Ukraine limit its armed forces to 85,000 troops, cap the National Guard at 15,000, and impose strict limits on weapons systems — including no more than 342 tanks, 1,029 armored combat vehicles, 519 artillery pieces, and 102 combat and auxiliary aircraft. Ukraine’s arsenal would also have been restricted to weapons with a maximum range of 40 kilometers.

Of course, the sides did not reach an agreement. Ukrainian negotiators in Istanbul proposed a force of 250,000 troops and much higher caps on weapons: 800 tanks, 2,400 armored combat vehicles, 1,900 artillery systems, and 160 aircraft. They also suggested setting the maximum range of artillery and missile systems at 250 kilometers. Current peace proposals, as far as is known, do not address weapons inventories or strike ranges at all.

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

The current peace proposals under discussion no longer include restrictions on certain types of weapons for the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Any limits on the size or quality of Ukraine’s military are meaningless, however, without adequate resources. In the years 2026-2027, Ukraine will require at least $60 billion in external financing, though some estimates range far higher. For example, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has put Ukraine’s needs over the next two years at €135 billion. Maintaining one Ukrainian service member costs about 1.2 million hryvnias a year, based on 2024 estimates — nearly $30,000 at current exchange rates.

An army of 600,000 would require about $18 billion annually in personnel costs alone, while an 800,000-strong force would cost roughly $24 billion a year. These figures do not include spending on weapons, ammunition, logistics, or infrastructure. While military outlays during peacetime costs would naturally decrease — due to the absence of various “combat” payments, compensations for injuries, and other payouts — it will still amount to tens of billions of dollars.

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

Until now, frozen Russian assets have been seen as the only plausible source of funding for a large, well-equipped Ukrainian military. On that assumption, Ukraine signed memorandums of intent (1, 2, 3) for expensive weapons purchases, including 150 Swedish Gripen fighter jets, 100 French Rafale jets, and U.S.-made combat helicopters. Those frozen assets were also expected to help cover soldiers’ pay and were viewed as a primary, if not the sole, source of funding for Ukraine’s broader budget, not just defense.

Under the Witkoff–Dmitriev plan, however, the frozen funds would instead be directed toward Ukraine’s economic reconstruction and to a joint U.S.-Russian investment fund. Talks in Berlin failed to produce a unified position on the issue, as European countries were reluctant to seize the assets outright, citing serious legal precedents and unpredictable risks. Leaks suggest the U.S. administration also opposes using the funds without Moscow’s consent.

Europe has instead opted for a compromise: the assets will remain frozen indefinitely, and Ukraine will receive a €90 billion loan secured against them. That arrangement, however, is likely to force a return to the unresolved question of the assets’ ultimate fate as soon as the currently allotted funds run out. Absent such funding, Ukraine’s only alternative to maintaining a large peacetime army would be robust security guarantees. But those, too, remain undefined.

The original Witkoff-Dmitriev plan did include the phrase “reliable security guarantees,” and with input from Dmitriev himself, Axios later reported that the proposal envisaged time-limited assurances that were nevertheless “in the spirit” of NATO’s Article 5. Of course, NATO membership itself would be the strongest possible security guarantee, but the 28-point plan explicitly demanded that Ukraine enshrine in its constitution a clause prohibiting Kyiv’s accession to the North Atlantic alliance.

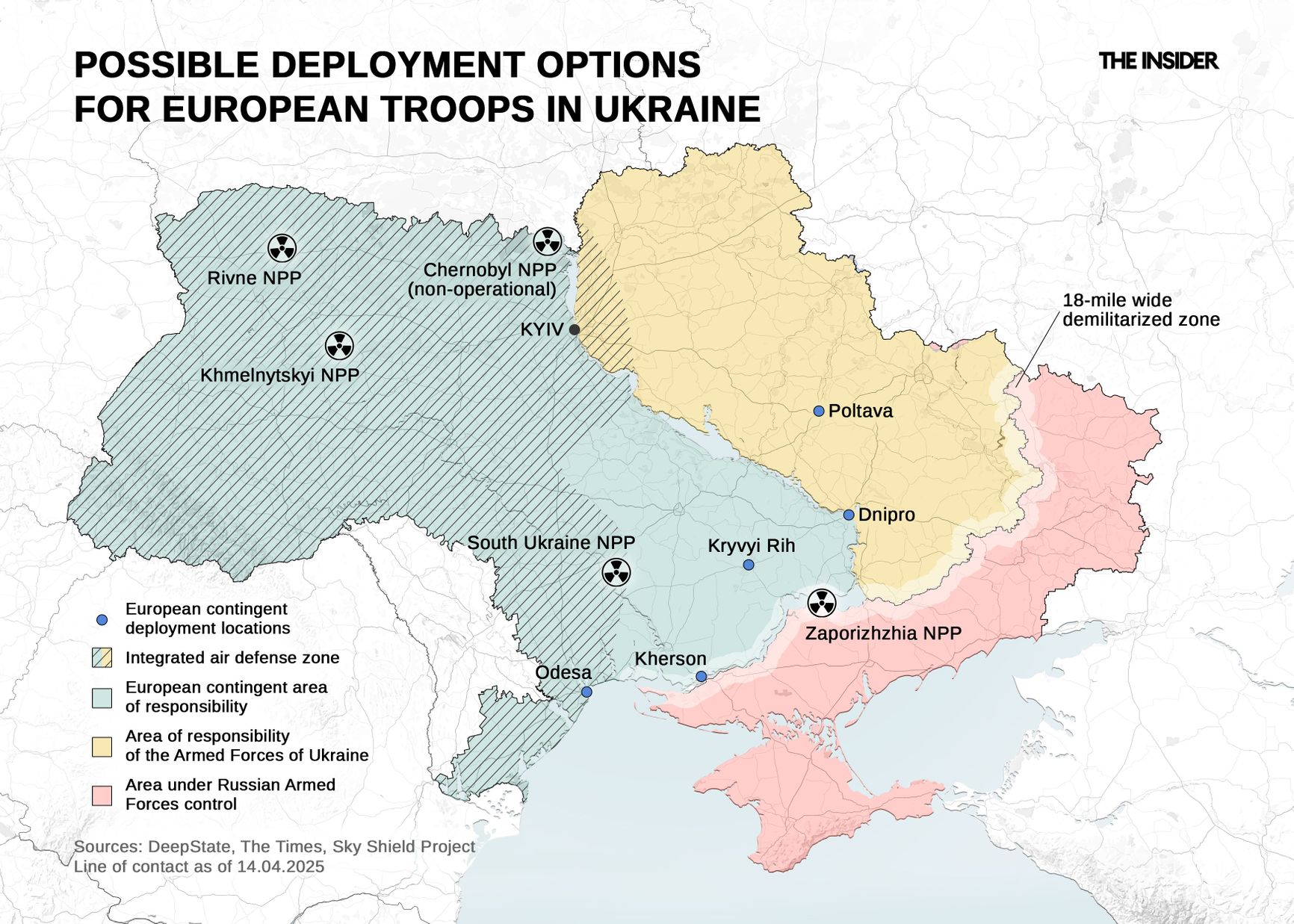

According to leaks published by outlets such as The Washington Post, the talks in Berlin produced agreement on a so-called “platinum standard” of guarantees approximating Article 5, which would be put to a vote in the U.S. Congress. However, details of how these guarantees would work and what they would include remain unclear. Another option for effective and credible (i.e. entirely unacceptable to the Kremlin) guarantees would be the deployment of troops from guarantor countries on Ukrainian territory. The 28-point document included a compromise provision on “fighter jets in Poland,” an apparent reference to the “coalition of the willing” plan to help control Ukraine’s airspace without a physical troop presence on the ground.

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

The talks in Berlin produced agreement on a largely undefined “platinum standard” of security guarantees for Ukraine.

European participants in the talks confirmed plans to create “multinational forces” tasked with assisting the modernization of Ukraine’s military, controlling air and maritime space, and monitoring a ceasefire. In essence, this repeats initiatives first put forward in the spring of 2025, which The Insider analyzed in detail at the time. As then, implementing such measures without U.S. support would be difficult. It is also unclear what would persuade Vladimir Putin to drop his objections to the involvement of “NATO troops” in military and technical cooperation with Ukraine — something the Kremlin typically describes as the “military takeover” of Ukrainian territory. Putin launched the full-scale invasion demanding Ukraine’s “demilitarization,” making it hard to imagine him agreeing to end the war by formally inviting NATO forces into the country.

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

Another important element concerns global strategic stability. After Putin and Trump exchanged threats in early November about resuming preparations for nuclear weapons tests, the 28-point plan put forward a provision on extending the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), which was signed in 1991 before being superseded by subsequent agreements. The current New START treaty, which expires in February 2026, limits the two parties’ to 1,500 deployed nuclear warheads, while the original 1991 agreement placed the cap at 6,000. Given that the 28-point plan was largely drafted by non-experts, it is possible that the reference to START I was made in error, as a return to the 1991 provision would actually allow for a significant increase in the nuclear arsenals of each country.

The parameters of a potential peace agreement on Ukraine are meant to serve one goal: ending the conflict and preventing its resumption in the near future. The core problem is this: the Kremlin’s demands for military restrictions on Ukraine’s armed forces are seen in Ukraine and among its Western allies as maximalist, while Putin treats them as baseline conditions. As a result, there is little prospect for convergence.

After the Berlin talks, U.S. officials said in a briefing that 90% of disputed issues had been resolved. It is clear, however, that this does not include the most critical 10%: the fate of Donbas, the size and capabilities of Ukraine’s armed forces, and security guarantees from Kyiv’s international partners.

In any case, a necessary — but, by itself, insufficient — condition for any durable settlement is the presence of credible guarantees from Western countries, either financial (to sustain Ukraine’s independent defense capacity) or military (to provide deterrence). And yet, absent any indication that the status quo has become truly unsustainable for either side, all signs point to a continuation of the war for the foreseeable future. The full-scale fighting has already endured for three years and ten months — longer than America’s fight against Japan in WWII (three years and nine months) and one month shy of the length of the Soviet Union’s struggle against Nazi Germany (three years and eleven months).

DeepState is a Ukrainian project that maintains a regularly updated map of territories under control in the combat zone in Ukraine and publishes reports on the situation at the front based on open sources (OSINT) and information from the Ukrainian military.

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari