Activists from WalkFree, an international human rights group that aims to end modern slavery, estimate that roughly 1.9 million people in Russia are being kept in some form of bondage. St. Petersburg alone has hundreds of so-called workhouses, and thousands more are scattered all across the country. Almost all of them operate illegally, and workers are forced to labor for humiliatingly low wages — or for free. Some of these houses are disguised as religious communities or rehabilitation centers and even receive impressive government contracts. Residents who wish to leave and find a normal job are often severely penalized. Meanwhile, workhouse owners make millions, living lives of luxury.

Content

“People in desperate circumstances”

“Like prison”

Jobs at all costs

Violence in workhouses

How much does a workhouse bring in

Rats and internal coordination

Masquerading as rehabilitation centers

Homeless on government contracts

Ties with Kemerovo gangs

Connections with the Russian Orthodox Church

The interviewees' names have been changed to protect their identities. The real names are known to the editors.

Late at night, a warming station for the homeless on the outskirts of St. Petersburg begins to serve dinner: potato soup in plastic bowls, with a side of black bread. In frosty weather, food gets cold almost instantly. The homeless are trying to get warm, huddling around wood stoves in tents. An old Russian pop song blasts from the radio in the background. More and more people are gathering.

“A workhouse is a slave house,” homeless people lining up for a hot meal told The Insider. “We have better food here than they do.”

“They took away my documents and locked me up. I barely escaped and had to apply for a new passport,” a man says. He appears to be in his 40s and wears clean, branded clothes. He says his name is Anton. Anton's story is like many others told here in the tents: he lost his apartment, had to live on the street, couldn't find a job, and ended up in a workhouse.

A homeless man eats soup at a warming station

“People in desperate circumstances”

Illegal advertisements for workhouses pepper walls all over St. Petersburg. The ads promise “help in a difficult life situation”: free housing, food, and most importantly, daily payouts. Such promises appeal mainly to homeless people, migrant workers, victims of fraud, and ex-cons — those who have nowhere else to turn.

“I'm from Belarus,” Viktor explains. “About six years ago I came to St. Petersburg to earn money. I was in the restoration business, making good money. But I started drinking and using drugs. I got kicked out of work and ended up on the street. I didn't feel like going home. So my friends and I decided to call the number on the business cards.”

As it turned out, promises of help in workhouses always come with very strict demands. All workhouse residents had to work eight-hour shifts every day at whatever location the workhouse assigned for them.

"Are you in a difficult situation? Living on the street with no money? Stalker Work Association." The center of St. Petersburg is overflowing with such ads.

“At the time, construction workers and laborers earned 2,000 rubles [a day - $20] in cash. But the first workhouse offered me 250 rubles [$2.5] per shift, and at the second, they told me to work six days for free and I would only earn something on the seventh day,” Viktor says. Eventually, he settled for a workhouse that offered roughly $5 a day.

To compare, the minimum monthly wage in Russia is equivalent to $224, meaning that any employer who pays less than $10 a day for a full-time job is breaking the law, even if the labor is not forced.

Aside from ads, workhouses recruit workers in person. They seek out candidates at railway stations, on trains, and at homeless assistance facilities. “If you spend a night at a train station, they'll come up to you 40 times, offering help. They look for people who appear lost,” Anton says.

A large, bearded man named Boris interjects: “I was on a suburban train from Peterhof to St. Petersburg to see my daughter when two guys came up to me and offered a job: 'It's okay, not too hard. You'll rest and come to your senses.' I fell for it and went there.” Boris explains that after he got divorced, he left the apartment to his wife — a decision he regrets. “I'm already in my sixties. It's tough living on the street,” Boris admits.

“I was in business, but they took everything away from me and left me on the street,” explains a homeless man named Marat, who is hesitant to speak about himself. “Workhouses are horrible. But when it's -20°C outside, and you realize that you can freeze to death and have nothing to eat, you have to choose: either work for a while in exchange for food and shelter, get yourself in order, and then somehow get back on your feet — or freeze in the street. For most people, this is the only motivation.”

When it's -20°C outside, and you have nothing to eat, you have to choose between toiling in a workhouse and freezing to death

“Like prison”

Workhouses in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and other large Russian cities are similar to one another. As living quarters, they use detached houses or three-room apartments — and sometimes even basements, according to our homeless interviewees. An average institution houses and employs from 12 to 30 people. “There were bunk beds in the bedrooms, with a distance of about a meter between the beds. Not too cramped, I guess. Like in prison,” Viktor says.

Marat counters: “It's cramped and disgusting. Not everyone's clean. Some have lice. Normal houses take care of it. When someone comes in off the street, all of their clothes go straight into the furnace. They get a shower and shave. If lice are visible, their head is shaved. But some houses still get lice.”

“That's where I had my first run-in with bedbugs. I didn't even know what these creatures were,” Viktor adds.

Even if housing conditions are bearable, all workhouses economize every possible cent on food, former workers say. The residents are fed just enough to give them the strength to work. As a result, people are hungry all the time. According to Viktor, who has lived in three workhouses, all used the cheapest vegetables and cereals, often those that had passed their expiration date. Twenty people could be fed for days with broth from one chicken.

Workhouse residents are fed just enough to give them the strength to work

Alcohol and drugs are strictly prohibited in all workhouses. If someone is caught drunk, they can be stripped of several days' worth of revenue. Another prohibition is sleeping away from the workhouse. “It was a manipulation on their part. At 11 p.m. [the house management] locked the bars and you couldn't even go out into the lobby for a smoke. For a smoker, especially in a situation like this, smoking is the only way to unwind. And when you can't do something, you want it even worse,” says Viktor.

Each workhouse is run by a supervisor and an assistant who is effectively his right-hand man. Elders are also appointed from among the most responsible workers. They monitor other residents and accompany them to their assigned jobs. The house may also employ a few women living in separate quarters. They do the cooking and cleaning. Often, several workhouses will form a network managed by a single “CEO,” Viktor says.

As he recalls, in his second workhouse, the manager offered him the role of assistant. His additional duties included putting up ads around town, answering the phone, buying food, and keeping an eye on workers on the job. As Viktor says, he received no extra money and continued to perform assigned jobs on par with others, but at least he was allowed to go out for a smoke at night.

Jobs at all costs

Workhouses in large cities make money by sending crews of residents to perform various jobs. They can be in construction or repairs, demolition of varying complexity, working as movers and laborers, snow removal, and even working as plumbers and electricians. Workhouses look for contracts on the Avito classifieds portal, social media sites, and Telegram. They also publish ads offering their services. Everything is done unofficially, without employment or the payment of taxes.

Workhouses look for both workers and customers

“All major real estate developers hire illegals without official registration, so if something happens, no one is responsible for them. If a worker falls from a height, they will likely just dump his body outside the fence,” Marat says.

Laborers travel to jobs together with a senior worker, usually by public transport. “They give you two tokens for a return trip, and also a sack lunch,” Viktor says. One of the first jobs he was assigned to was out of town:

“It was winter, and it was freezing cold. We took the bus. The job was screwing bolts in the middle of nowhere. We were out in the open, and the wind was howling. There were only two cabins, both without heating. All the food we had with us froze. Pea soup turned into a chunk of ice.”

Once the workhouse accepts a job and sends a crew, you cannot leave — the job must be done at any cost, former workers say.

Once the workhouse accepts a job and sends a crew, you cannot leave — the job must be done at any cost

“We kept getting jobs normal people wouldn't do for any money. We had to carry fire doors to the 24th floor through a narrow ladder. Each weighed over 100 kilograms, and there were four for each floor. We were all barely standing. Only willpower kept us going,” Viktor recalls.

“I saw so-called foremen kicking people and saying, 'You're slacking off, you can do it,'” Boris says.

Violence in workhouses

According to volunteers who work with the homeless, violence is on the decline in the workhouses of St. Petersburg, Moscow, and other major cities. But in remote regions, the situation is much worse.

“When workhouses first emerged, violence was rampant there,” says Andrei Ponomarev, a volunteer with a charity helping the homeless. “People often worked without any payment and had their papers taken away. Sexualized violence and other degrading practices were present. There were beatings that sometimes ended in murder.”

Today, rather than using physical force, workhouses are more likely to employ psychological abuse and methods of total control. “You can't go anywhere. You can't do anything. Even on your day off, you'll just sit there. The point is that they don't let you go anywhere,” Anton says. The only purpose of workhouse residents is to work and generate income.

How much does a workhouse bring in

A workhouse is a highly profitable business with minimal costs. The Insider calculates that a ten-strong crew brings the workhouse a net income of nearly $5,000 a month. According to former workers, all managers and CEOs earn enough money to buy apartments and cars rather quickly, and some “invest in the business,” expanding the network of workhouses and opening new branches.

Assistants from the Leader Workhouse

Social media

Workhouse managers and their assistants, whose phone numbers are listed in ads, often post photos on social media that show them posing with expensive cars, dining in restaurants, and vacationing at resorts.

Rats and internal coordination

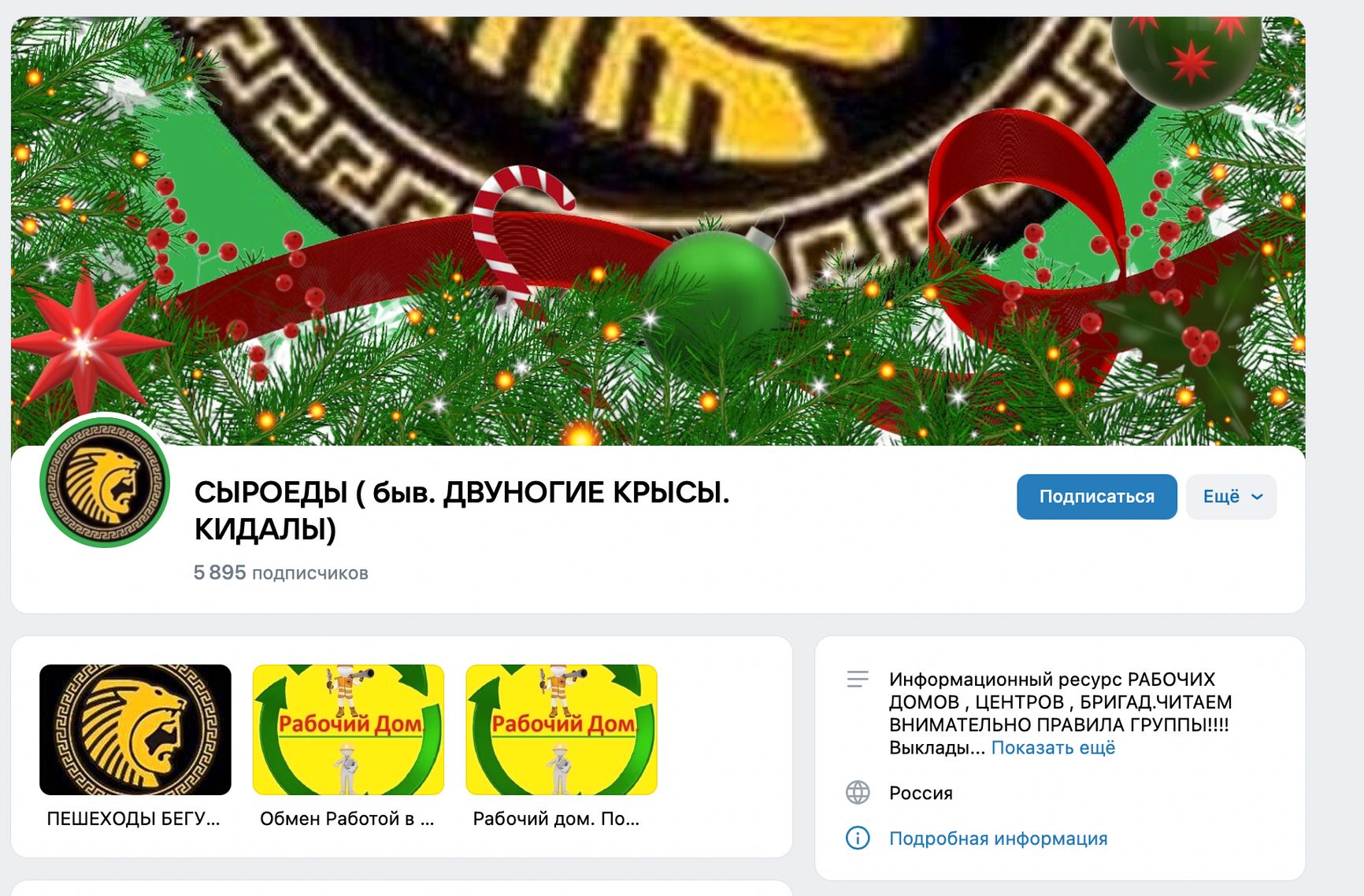

According to former workers and volunteers, most workhouses coordinate with each other, using chat rooms and social media groups. There, they can discuss jobs or share information about fugitive workers, making blacklists.

“You could call it a community in a sense. but we don't see any hyperstructures behind it. Most likely there aren't any,” volunteer Andrei Ponomarev says. “When a new worker joins the workhouse, their photograph is posted in the supervisors' chat room. It is a way of keeping track of people's whereabouts. For instance, he could be a thief who stole from his old group and ran away — such people are called 'rats,'” Viktor explains.

Workhouses communicate in online communities

Despite the rigid control system, workhouses struggle with very high turnover. Some old-timers have been there for up to seven years, but most leave after a few months. The worst thing for the workhouse management is when the worker doesn't just run away, but starts working for their customer directly. In this case, the workhouse loses both the worker and the money.

“I heard that there were threats, legs were broken, and physical violence was used against those who went to work for customers,” Viktor says. He himself admits that he “took the French leave” from workhouses twice. He simply went to work for the customers and even brought some of his peers along with him.

Masquerading as rehabilitation centers

The modern model of workhouses appeared in the early 2000s in the city of Kemerovo, volunteers and former workers told The Insider. The concept was the brainchild of Andrei Charushnikov, a Kuzbass resident with a criminal past. In 2001, he founded Preobrazheniye Rossii (“Transformation of Russia”), an organization that promised to help alcoholics and drug addicts.

However, in reality, under the guise of a rehabilitation center, Charushnikov created slave houses, where physical labor was the only form of therapy. Workers were not getting paid, and it was almost impossible to leave. By 2011, the network had grown to 400 branches nationwide. However, ten years later, law enforcement authorities finally took an interest in the organization, and in 2013, a court in Kemerovo found Charushnikov and several of his assistants guilty of multiple counts of kidnapping — and one murder. The founder of the workhouses was sentenced to nine years in prison.

Andrei Charushnikov, the founder of Russia's first workhouses, should have been released by now

Although Preobrazheniye Rossii was shut down, similar organizations continue operating. Some of them still work under the guise of rehab centers, promising treatment for addiction and a return to normal life — while enriching themselves off the slave labor of their purported beneficiaries.

“They don't pay you any money, make you pray morning and evening, keep you under lock and key, and forbid smoking. The first time I went to such a house, I was lucky to have a manager who had also been to war, and I was able to quietly leave,” Boris recalls his experience in one of the houses.

Homeless on government contracts

Most workhouses operate completely illegally. Even if a company has been registered as a legal entity, this does not mean that it is working officially. For example, the website of Vozrozhdenie, which ostensibly specializes in the rehabilitation of alcohol and drug addicts, claims that the organization has branches in 48 Russian cities, including in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Even if a company has a legal entity, it does not mean that it is working officially

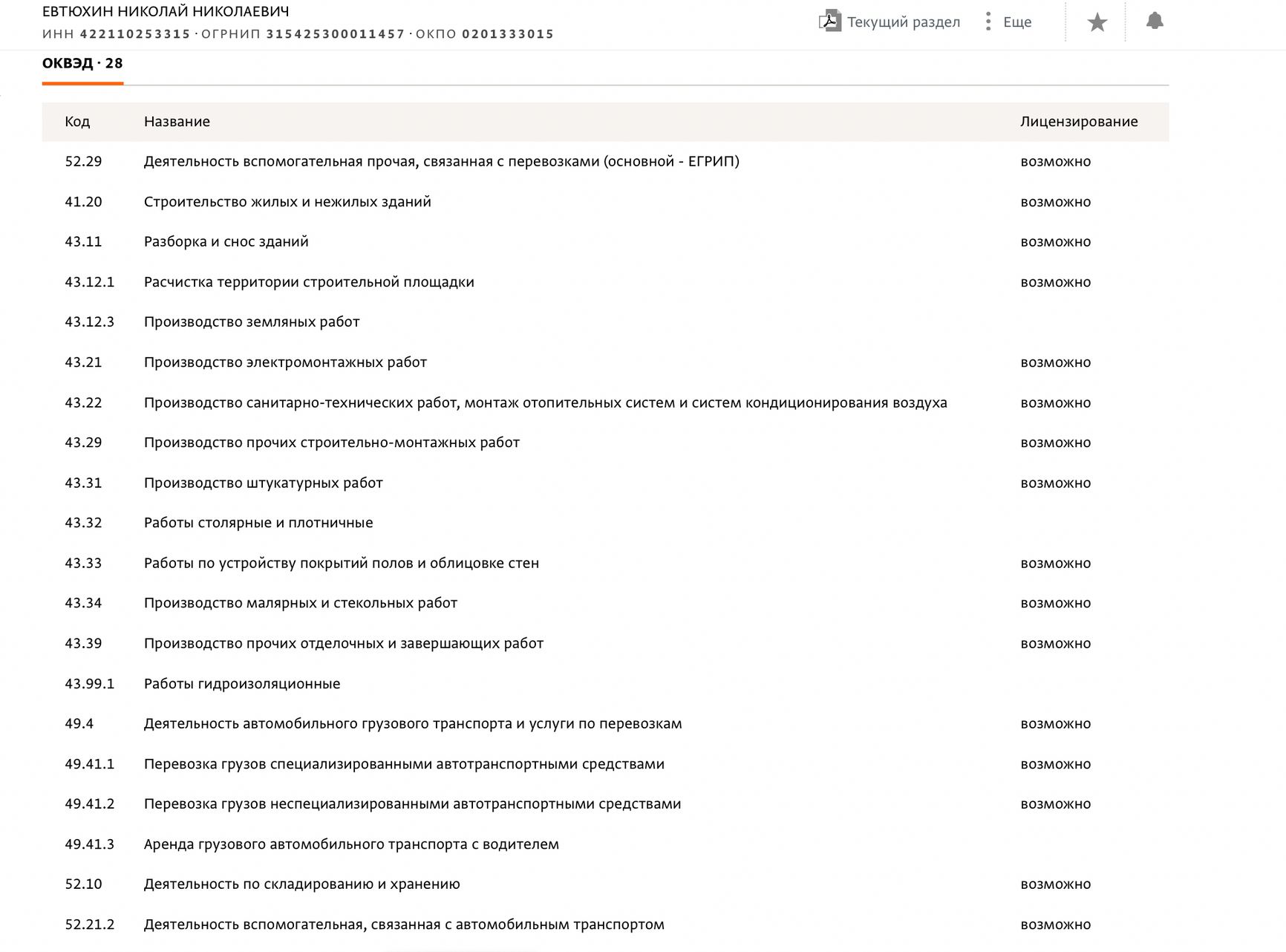

However, according to the SPARK database, Vozrozhdenie is a Barnaul-based microenterprise with a turnover of only $2,500 per year. Its listed CEO is Nikolai Yevtyukhin, a native of Kuzbass. In addition to being the frontman of a nominal legal entity, Yevtyukhin is a sole proprietor offering a wide range of services, from repair work to cargo transportation. As a sole proprietor, he gets orders and sometimes even government contracts.

SPARK data on sole proprietor Nikolai Yevtyukhin

Thus, in 2016 and 2017, Yevtyukhin received three government contracts with the Kuzbass-based Ritual for a total of $35,000. According to the contract, his sole proprietorship sent crews of workers to undertakers for two years to “organize funerals” and carry the bodies of the dead.

Yevtyukhin himself has long since moved to Lyubertsy outside Moscow and, according to his wife's social media accounts, the family has bought an expensive Toyota Land Cruiser Prada and has taken vacations at the seaside.

Yevtyukhin and his wife

Social media

Yevtyukhin driving his car

Telegram bots

Ties with Kemerovo gangs

Another major workhouse network, Tvoy Dom (“your home”), was also embroiled in a scandal. In August 2023, volunteers of the Alternativa Anti-Slavery Movement freed several people who had been forcibly kept in the organization's Tver branch. The workers were locked in a two-story private house behind a high fence and forced to work for free.

Tvoy Dom is registered in the Leningrad Region and claims to specialize in the “social adaptation of citizens.” It is headed by one Dmitry Zozulya, who previously led the Voronezh branch of the above-mentioned Preobrazheniye Rossii. Incidentally, Tvoy Dom was registered in 2013, the same year the court in Kemerovo passed the verdict on the leaders of Preobrazheniye. The organization's website lists Zozulya as its president. While the slaves in Tvoy Dom work for free, receiving barely enough food, Zozulya leads the luxurious life of a millionaire.

According to former homeless people and volunteers, several St. Petersburg workhouses are connected in one way or another to former Preobrazheniye Rossii organizers or are run by former prisoners.

Zozulya and his friends

Social media

In 2019, Russian TV channel 78 aired a story about the Svetly Put (“bright path”) Labor Home. Former workers told reporters that the management not only held residents by force, but also beat those who refused to work. According to them, some homeless people were even sent to work in other regions.

Connections with the Russian Orthodox Church

More often than not, workhouses with a religious profile are not affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church in any way. Workers are simply made to pray several times a day. A notable exception is the Noy (Noah) Workhouse. However, according to volunteers working with the homeless, while these establishments may treat the homeless more humanely than others do, they are no better than other workhouses, as they, too, exploit people in desperate situations.

The Noy Workhouse cooperates with the Russian Orthodox Church. “It pays 300 to 500 rubles per working day in cash. You are free to leave, but even if the workhouse does not practice violence, coercion, or confiscation of documents, it still keeps workers on the verge of survival, paying them just enough for food, not more,” says volunteer Ponomarev.

From a legal standpoint, payment for labor below the minimum wage violates Russian laws, regardless of whether the labor is voluntary or not.

Noy has been operating since 2014. It was founded by people with close ties to the Russian Orthodox Church, including the former rector of a Moscow suburb church, Andrei Kovalchuk. However, even the most humane workhouse cannot give the homeless what they most need when they arrive seeking help.

Even the most humane workhouse cannot give the homeless what they need most

“Although people are promised that they will save up money and be able to leave and get on with their lives somehow, in reality, this hardly ever happens. There are no stories of someone working for food and shelter and somehow saving up enough money to rent an apartment and get a fresh start. At least I haven't heard any. Because no workhouse is actually interested in it,” Andrei Ponomarev sums up the situation.

Of all the interviewees The Insider spoke with, only Viktor was able to leave the workhouse, rent a place to live, and settle down with his family. Anton and Marat are working illegally and living in night shelters. Boris is trying to sue his ex-wife in an attempt to get his apartment back.