Deutsche Jugend voran! Telegram channel

Deutsche Jugend voran! Telegram channel

Neo-Nazi and fascist slogans are becoming increasingly visible in the public sphere of the European Union. The unprecedented success of France’s National Rally, the growing support for Germany’s AfD, and the rise of Spain’s Vox are in no small part due to their appeal to young voters. In broad terms, the radicalization of the younger generation is fueled by two main factors: economic insecurity and social media algorithms that amplify far-right disinformation. As The Insider found in Spain, Germany, Croatia, France, and Italy, the rightward shift in EU countries is driven largely by the same causes — though each nation has its own specifics.

“United, Great, and Free!”

“Our people come first”

“For our Homeland, we are ready!”

“Build while everything is falling apart”

“Fascists of the third millennium”

A right-wing future

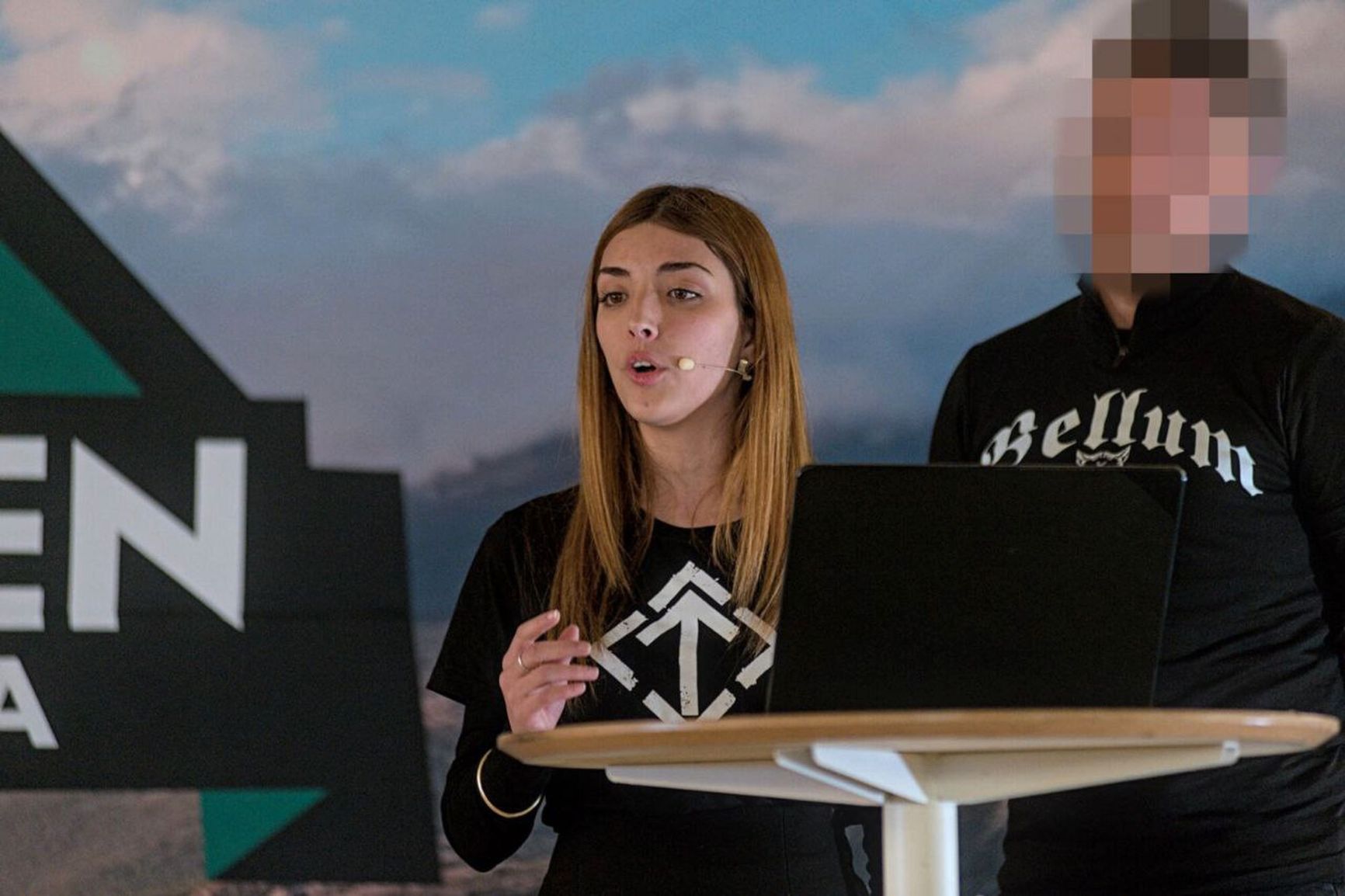

In April 2025, 23-year-old Spanish neo-Nazi Isabel Peralta was sentenced to one year in prison for inciting hatred against Muslims and Moroccan migrants. She was put on trial for holding a rally outside the Moroccan Embassy, where participants shouted slogans such as “Death to the invaders” and, “This is not migration, this is an invasion.”

Peralta responded to the verdict with a quote from Goebbels: “There will come people who will try to follow our path and will be persecuted just as we were. But in the end, we will triumph, because what is good and true always prevails in this world.”

Peralta is a leader of the Spanish neo-Nazi organization Bastión Frontal. The press has dubbed her the “muse of the Falangists” — a reference to the Spanish far-right movement that sprang up in the 1930s. Peralta defends Hitler and has repeatedly displayed Nazi symbols in public. For this, she has been permanently banned from entering Germany, where she once attempted to bring in a copy of Mein Kampf and a flag bearing a swastika.

Bastión Frontal emerged in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic and operated exclusively on social media, spreading xenophobic statements and memes. Its activists called for the defense of the Spanish nation, which they claimed was under threat due to the government’s immigration policy.

After the group's X (Twitter) and Instagram accounts — which had a combined following of more than 20,000 — were suspended, its activities continued on Telegram, a platform far more tolerant of such content.

As the main target of their attacks, the radicals chose so-called “unaccompanied minor migrants” (menas), who were said to have placed a burden on taxpayers while posing a threat to society. (The influx of these minors has indeed become a serious challenge for Spain — one that has no quick fix.)

When the organization was founded, Peralta was 18, and her associate Rodrigo Miguélez was 19. Bastión Frontal claimed to have attracted around a hundred activists aged 15 to 25. At a certain point, their activity spilled onto the streets, but despite tens of thousands of followers on social media, Bastión Frontal rallies drew no more than 300 participants.

In 2022, after just two years of existence, the organization announced its dissolution due to a lack of activists and funding. However, Peralta continues to maintain an active presence on Telegram and TikTok — and to give interviews — all while appealing her sentence.

Recruitment takes place at hand-to-hand combat classes, which are openly positioned as part of the preparation for defending the nation

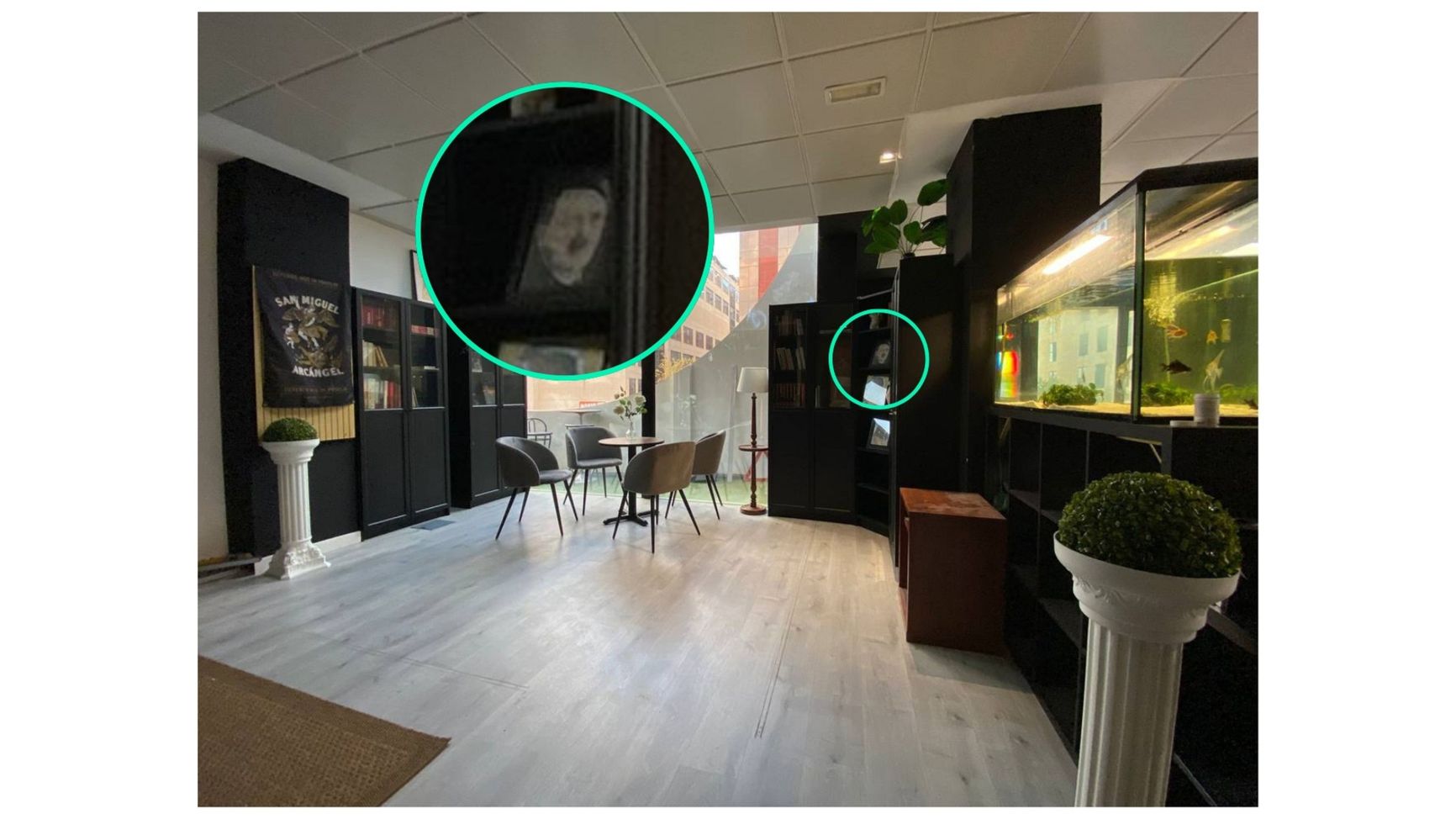

The far-right organization Núcleo Nacional (“National Core”) is in far better financial shape. In July 2025, it opened a headquarters in Madrid with a floor area exceeding 500 square meters. The premises, which features a bar, a library, and a gym, is called “The Nest” in honor of Adolf Hitler’s alpine Kehlsteinhaus retreat.

Núcleo Nacional is registered as a cultural and sports association, and it does, in fact, help young people with physical training — though with a strong ideological component. Recruitment into the organization takes place at hand-to-hand combat classes.

The trainers openly position the workouts as part of the preparation for defending the nation. They also make no secret of the organization’s neo-Nazi orientation — the headquarters is decorated with portraits of Hitler.

On social media, Núcleo Nacional posts training videos that portray migrants and left-wing activists as opponents. Some of these clips include explicit calls for “active defense of the streets” and “countering hostile elements.”

The organization is led by the aforementioned Isabel Peralta, along with Enrique Lemus and Iván Rico. Lemus is a veteran of the far-right movement, with extensive connections among neo-Nazis and neo-fascists across Europe. Rico’s identity remains unknown — he always conceals his face behind a mask at public protests.

Núcleo Nacional is opening branches across Spain and running an active social media campaign, though the number of active members so far barely exceeds 300. Police have stated that the organization in many ways resembles a paramilitary group.

The main factor pushing young people into the ranks of far-right parties and movements is well known: economic instability. Spain has one of the highest youth unemployment rates in Europe and a high average age for leaving the parental nest — 30.4 years. Only Croatia, Greece, and Slovakia fare worse in that category.

The main reason young people are drawn to far-right parties and organizations is economic instability

Starting an independent life requires an extremely high basic income. However, Spanish youth are faced with instability and an uncertain future. According to studies, every other Spaniard aged 20 to 24 works temporary or part-time jobs. As a result, in some cities, young people spend more than 92% of their income on rent.

At the same time, Spain’s economy is showing rapid growth — four times the EU average, despite a housing shortage, a lack of jobs, and sluggish wage growth. Reports of this economic rise only fuel frustration with the worsening quality of real life, even as the statistical indicators keep going up.

Meanwhile, neo-Nazis glorify the economic achievements of Francoist Spain: “millions of social housing units, infrastructure we still use today, bonuses for workers, family subsidies, and pensions.” Modern Spain, by contrast, is portrayed as nothing more than “a tourist destination with no industrial potential.”

The now-defunct Bastión Frontal repeatedly called for resistance to precarious living conditions but offered nothing beyond slogans. Similarly, Núcleo Nacional has no economic program that goes beyond criticism of the EU’s financial policies.

The far-right Vox party echoes these complaints while promising affordable housing, lower unemployment, and tougher migration policies — measures that, at the very least, would reduce competition in the lower segment of the labor market. In their rhetoric (though not in their official platform), Vox representatives even call for the expulsion of millions of migrants from the country.

Simple messaging and the fiery speeches of party leader Santiago Abascal have made Vox exceptionally popular on TikTok. Teachers note that when discussing certain topics with students, they feel as if they’d been transported back decades — the younger generation, it would seem, now shares the values of their grandparents.

According to CIS polls, Vox is Spain’s most popular party among voters aged 18 to 25, polling at an all-time high of 17.4%. If parliamentary elections were held in 2025, Vox would take third place, just as it did in the 2023 elections. However, the current trend suggests that things could change before the next vote, scheduled for 2027.

Despite a number of legal restrictions, Germany is home to a range of far-right organizations — all of them primarily targeting young audiences. As in Spain, they are small in number but active on the streets.

The most visible among them are Deutsche Jugend Voran (“German Youth Forward,” DJV) and Jung und Stark (“Young and Strong,” JS). Both organizations primarily attract young people, including teenagers aged 14 to 18.

The main target of German neo-Nazis is queer people rather than migrants

Jung und Stark was founded in 2024 and, within just a year, became prominent enough to attract police attention. The organization is notable for operating on a franchise model — a decentralized structure that consists of numerous small cells coordinated through messenger apps.

The main target of German neo-Nazis is not migrants, but queer people. They organize counterprotests alongside Pride events, shouting homophobic slogans. Since Pride marches follow a well-known calendar and are large-scale by nature, they inadvertently make far-right actions more visible.

Germany has one of the highest levels of support for same-sex marriage in the world, to go along with extremely high levels of tolerance overall. Measures of hostility remain relatively low, with survey data showing negative attitudes focused toward Syrians (18%), Turks (14%), and homosexuals (14%).

So far, neither JS nor DJV has managed to disrupt any events, but that does not signify failure. Every street action is converted into online content, offering activists valuable experience in digital mobilization.

Federal authorities note that these groups are radicalizing rapidly and are ready to resort to violence. However, due to their anonymity and decentralized structure, they are extremely difficult to track down. Nevertheless, in April 2025, a Berlin court sentenced the 24-year-old Deutsche Jugend Voran leader to three years in prison for causing grievous bodily harm. Hoping to identify his accomplices, police allowed him to remain free for two months after the verdict — but the effort yielded no results.

Until March 2025, Germany had a youth wing of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party — Junge Alternative (JA), comprising 16 regional branches with a total membership of around 2,500. JA built connections with other far-right groups, engaged in recruitment, and took part in street protests, spreading xenophobic and anti-immigrant propaganda.

The youth wing was considered more radical than the AfD itself and was eventually classified by German intelligence as a right-wing extremist organization. As a result, JA was dissolved — and the AfD began forming a new youth organization (this time within the party structure).

Then, in May 2025, the AfD itself was classified as a right-wing extremist organization, allowing intelligence services to conduct covert surveillance of the party and to recruit informants. However, the party was not stripped of its right to engage in political activity.

The AfD is pushing the boundaries of what is considered acceptable and gradually softening attitudes toward the crimes of the past. Its politicians argue that Germany’s culture of remembrance places too much emphasis on negative chapters, and that it is time for Germans to stop apologizing.

The generational divide is becoming increasingly visible. Germany has only about six million people over the age of 80 — those who can still be considered living witnesses of World War II. Consequently, the memory of the war relies less and less on personal accounts and family stories.

In Germany, the memory of the war relies less and less on personal accounts and family stories — and increasingly on the media

Despite all this, German youth remain optimistic and continue to trust state institutions. However, a quarter of respondents — mostly young people from eastern Germany — say they are dissatisfied and disillusioned with the status quo. The study notes that this audience is particularly susceptible to populism.

German authorities regularly ban, raid, and prosecute far-right parties and organizations. Yet the situation remains challenging. According to Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, in 2024 37,835 right-wing extremist crimes were recorded in the country — more than a hundred per day. The number of far-right extremists prone to violence exceeded 15,000.

The Ustaše (lit. “The Insurgents”) were a Croatian fascist organization that ruled the Independent State of Croatia from 1941 to 1945. In July 2025, at a concert by notoriously far-right Croatian singer Marko Perković (Thompson) in Zagreb, the singer shouted the Ustaše slogan — “Za dom spremni!” (“For our Homeland, we are ready!”) — from the stage.

The audience at Perković’s concert received the singer’s shout favorably and quickly joined in. The incident drew public attention due to record turnout at the event — upwards of 500,000 people (according to the organizers).

A European Commission spokesperson stated that investigating and preventing such incidents is the responsibility of the EU member state. The Croatian president also condemned the gesture. The opposition described Perković’s concert as a “disgusting neo-fascist Woodstock.”

No real consequences followed these statements, either for the organizers or for the performer.

The Ustaše slogan is punishable as incitement to hatred, but enforcement is highly inconsistent. In November 2013, shortly after Croatia joined the EU, footballer Josip Šimunić similarly shouted “Za dom” to fans (who responded with the customary “Spremni”) and was subsequently disqualified and fined 24,000 kunas (approximately $4,400).

However, in 2020, Marko Perković successfully defended in court his right to use the slogan in a song. The decision drew widespread criticism and did not set a precedent. The Ustaše salute remains prohibited.

Notably, in 2024, the mayor of Dubrovnik also uttered the slogan from the stage. Despite criticism, the official stated that he was not ashamed of his words and considered “Za dom spremni” part of the military symbolism of the 1990s. Ultimately, the mayor faced no punishment either.

Croatian youth are gripped by the same fears as their German and Spanish peers. In Croatia, these concerns are compounded by widespread dissatisfaction with pervasive corruption

Nazi symbolism in Croatia has already become an element of the subculture — primarily among football fans. Croatian neo-Nazis also operate in closed chat groups, but their street activity manifests not via rallies, but through music concerts. Their protests are too small-scale to be considered an actual movement.

At the same time, Croatian youth express the same fears as their German and Spanish peers. In Croatia, these concerns are compounded by widespread corruption: 54.6% of Croatians believe that personal connections matter more than competence when seeking employment. The country also has a high average age for leaving the parental home — 31.8 years.

In other words, the environment in Croatia is conducive to the rise of the far right, yet no significant phenomena have emerged.

According to the French Ministry of the Interior, 46 far-right organizations have been disbanded in the country since 2017, six of them in 2024–2025. The exact number of new groups is unknown — French neo-Nazis constantly change their names, merge, and split while very rarely ever officially registering.

Cells form around sports complexes, martial arts clubs, bars, and student work squads. Perhaps the only neo-Nazi group with its own headquarters is Tenesoun, which has no more than 100 members but has secured a prominent place in the media landscape.

Tenesoun has its center in Aix-en-Provence. It features a boxing section, lecture hall, bar, and even a garden. In addition to the standard far-right agenda, the organization emphasizes ecology and localism. Its emblem depicts a beaver, intended to symbolize a constructive communal spirit.

Despite their seemingly harmless image, Tenesoun members participated in an assault on a left-wing activist in 2022. Nevertheless, the Ministry of the Interior has not issued a decree to disband the organization. Such a move requires clear evidence, which apparently does not exist.

However, in many cases, disbanding a group achieves little. Radical activists easily flow into far-right parties, taking positions in Reconquête! and the National Rally (RN).

Reconquête! cannot boast significant popularity, with 5.5% of the vote and only five seats in the 2024 European Parliament elections. Shortly after that vote, the party experienced a split, expelling four MPs. Reconquête! is primarily known for its controversial frontman, Éric Zemmour — a far-right journalist and author who has repeatedly faced legal action for statements made against migrants. Despite substantial media exposure, he finished only fourth in the 2022 presidential election.

The National Rally (formerly the National Front) achieved a “historic” result in the European Parliament elections, winning 31% of the vote and securing 30 out of 81 seats. This success was due in no small part to the so-called “Bardella generation,” named after party leader Jordan Bardella, who succeeded Marine Le Pen as chair.

The thirty-year-old Bardella can rightfully be called a TikTok star, with 2 million followers. In absolute numbers, more than 500,000 voters aged 18 to 25 cast their ballots for his list.

Experts express concern that the electoral success of the far-right emboldens radicals, while others note that it is simply a symptom of “social malaise.” However, none of them can yet propose a remedy.

In June 2024, an investigation was published in the Italian press on Gioventù Nazionale — the youth wing of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s party. An undercover journalist attended a meeting of activists who openly called themselves fascists, performing the “Roman salute” and mocking politicians of Jewish descent. The exposé sparked a nationwide scandal, leading several members of the youth movement to resign.

A provision in the Italian Constitution reads: “Reorganization of a disbanded fascist party is prohibited.” As in France, Italy’s legal framework allows far-right organizations to be dissolved by decree. However, since 1952, the law has been applied only three times. By comparison, France has issued 46 dissolution decrees over the past eight years.

The largest neo-fascist movement in Italy is generally accepted to be CasaPound Italia (CPI), which got its start in 2003 when right-wing activists began occupying a government building in central Rome. The building had been empty, and the squatters set up a right-wing social center for low-income families. In practice, however, it became the headquarters of a neo-fascist organization.

CPI successfully presents itself as a helping community, not only to enhance its image but also to attract young people

In 2006, CPI attempted to rebrand itself as a political party and ran in several elections. However, its success did not go beyond the municipal level. In parliamentary, Senate, and European Parliament elections, CPI garnered less than 1% of the vote. In 2019, the organization announced that it was no longer a party and would instead focus on social welfare activities.

CPI has over 150 cells and approximately 6,000 members nationwide. The organization has a student wing, its own publication, and a volunteer branch that is involved in distributing food to low-income families, assisting disaster victims, and even planting trees. CPI successfully presents itself as a helping community, which not only improves its image but also helps the group attract young people.

At the same time, the organization’s activists have repeatedly faced criminal prosecution for robbery, assault, causing bodily harm, and engaging in the promotion of fascism. One of the most high-profile cases was the racially motivated murder of two Senegalese traders. The perpetrator, who committed suicide during arrest, had attended CPI meetings but, according to the organization’s own statement, was not a member. Nevertheless, at memorial events in Florence, where the tragedy occurred, mourners associated the killer with the group.

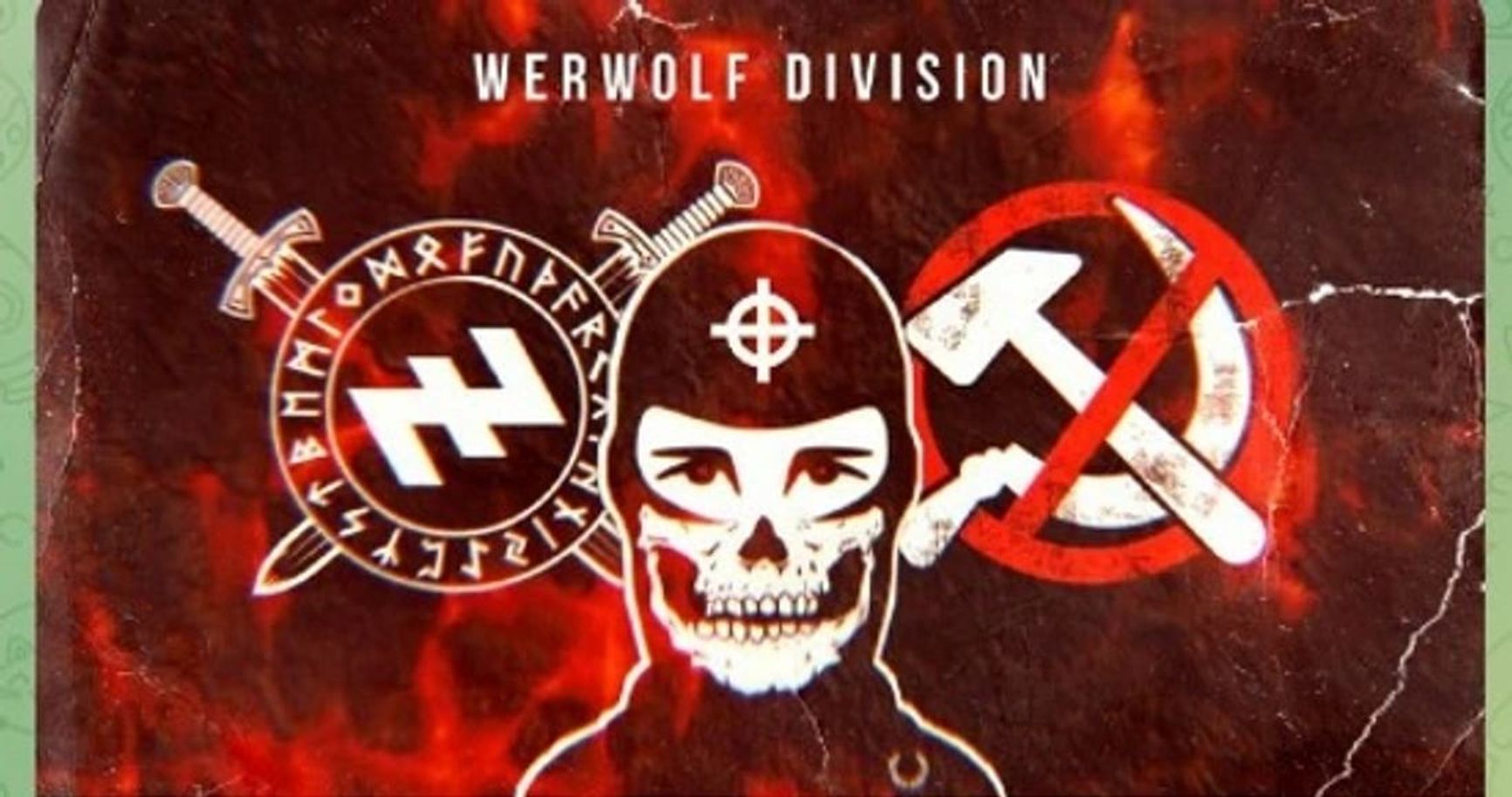

Italy is home to a number of other neo-fascist organizations. All of them, in one way or another, adopt CPI’s comprehensive approach and disguise themselves as charitable or educational organizations. At the same time, the most dangerous are location-independent online cells on Telegram — such as the neo-Nazi group Werwolf Division, a reference to the post-war Nazi underground of the same name.

In December 2024, police carried out 12 arrests and 13 searches in multiple Italian cities, seizing Nazi symbols and firearms from the suspects. The neo-Nazis had conducted propaganda through a network of Telegram channels and coordinated in private chats, where they had been plotting, among other things, an assassination attempt on Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

Meloni herself has stated that there is no place in her party for those nostalgic for the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. The prime minister has, of course, been presented with reminders of her party’s fascist roots and her past praise for Benito Mussolini, even as she now distances herself from neo-fascism not only in words, but in political actions. Under Meloni’s government, extremists have begun receiving lengthy sentences, and “Roman salutes” now lead to legal proceedings.

Overall, European neo-Nazi groups are small and, at first glance, do not seem to pose a serious threat. Typically, they are prosecuted for specific criminal acts rather than for their beliefs. Instead of being disbanded outright, they are placed under heightened surveillance.

However, these organizations create a subcultural environment in which anti-immigrant and xenophobic discourse is normalized — primarily through Telegram chats and TikTok content, which caters to younger audiences. The key role in this process belongs to personalized feeds, which are governed by algorithms designed to capture our attention and keep us online for as long as possible. In practice, this promotes the most emotionally provocative or controversial content. From the perspective of social media algorithms, right-wing content is more effective than left-wing posts. Different platforms have different patterns, but it is hardly coincidental that an internal Twitter investigation, conducted before Elon Musk acquired the platform, found that tweets from right-wing politicians and media outlets were amplified in algorithmic home feeds more than those from left-wing sources in six out of seven countries studied, including the U.S., the UK, and Canada. Similarly, a February 2025 study by Global Witness showed that home feeds on TikTok and X in Germany disproportionately recommended far-right content ahead of the federal elections. All of this, of course, can sway public opinion.

From the subculture, young people move into the youth wings of far-right parties, and from there into the parties themselves. In France and Italy, this trend is already evident, while in other countries, such as Croatia, it is only beginning to emerge.

In any case, the boundaries are becoming blurred: youth organizations are more radical than the parties themselves (AfD and Junge Alternative, Fratelli d’Italia and Gioventù Nazionale), neo-Nazi groups turn into political platforms and run in elections (CasaPound Italia), and Nazi slogans are entering the mainstream (the Ustaše “Za dom spremni!”).

The EU’s legislative and procedural framework is clearly unprepared for this. It will need to adapt — and soon.

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari